Chapter 11 Graphics in R Part 2: graphics

11.1 Scatter Plots

Begin by considering a simple and classic data set sometimes called Fisher’s Iris Data. These data are available in R.

'data.frame': 150 obs. of 5 variables:

$ Sepal.Length: num 5.1 4.9 4.7 4.6 5 5.4 4.6 5 4.4 4.9 ...

$ Sepal.Width : num 3.5 3 3.2 3.1 3.6 3.9 3.4 3.4 2.9 3.1 ...

$ Petal.Length: num 1.4 1.4 1.3 1.5 1.4 1.7 1.4 1.5 1.4 1.5 ...

$ Petal.Width : num 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.2 0.1 ...

$ Species : Factor w/ 3 levels "setosa","versicolor",..: 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 ...The data contain measurements on petal and sepal length and width for dim(iris)[1] iris plants. The plants are from one of three species, and the species information is also included in the data frame. The data are commonly used to test classification methods, where the goal would be to correctly determine the species based on the four length and width measurements. To get a preliminary sense of how this might work, we can draw some scatter plots of length versus width. In graphics, making scatter plots is simple:

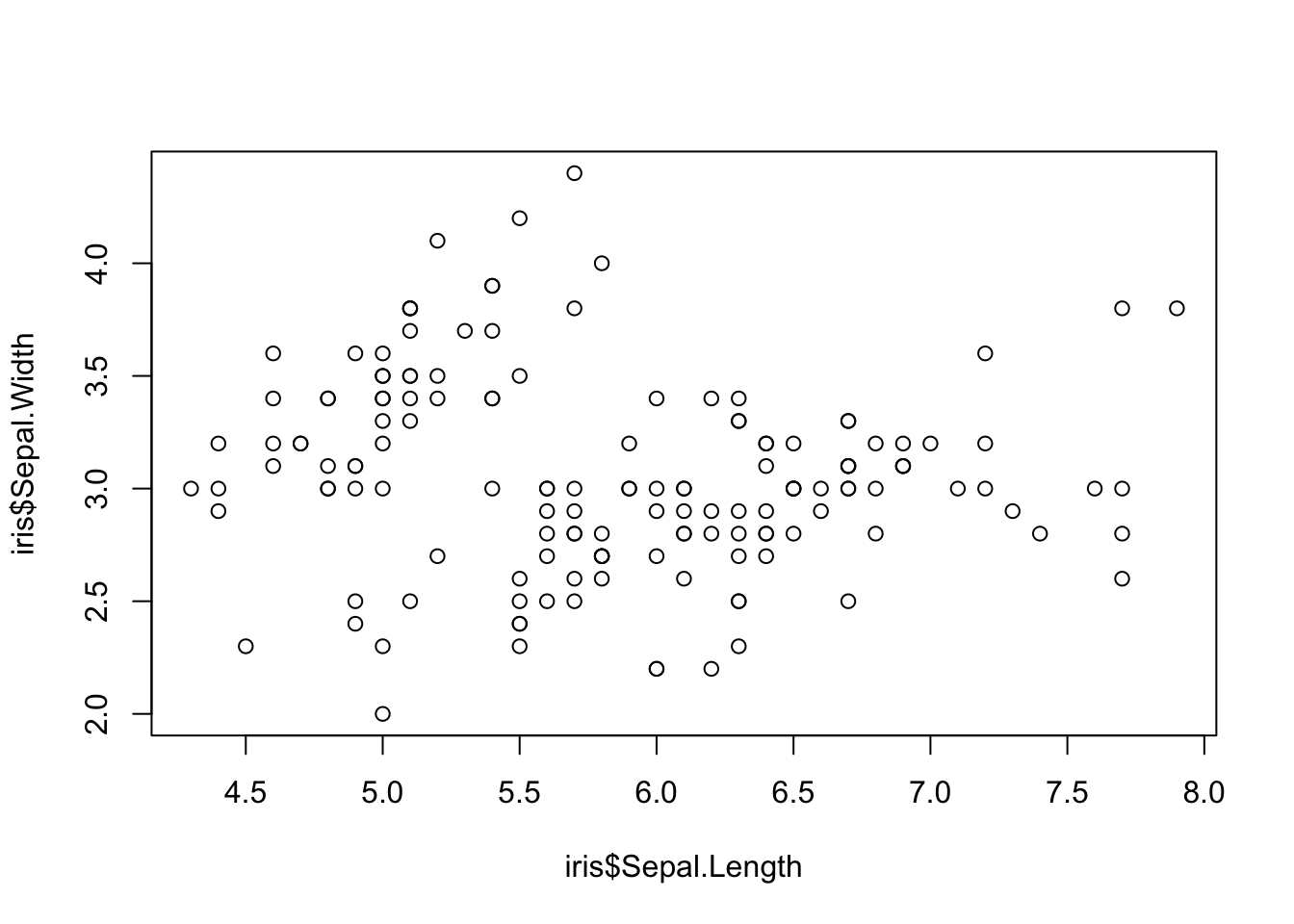

We see the plot() function by default creates a basic scatterplot when we supply the function with values for the x and y arguments.

Looking at the scatter plot and thinking about the focus of finding a method to classify the species, two thoughts come to mind. First, the plot might be improved by shading in the points. And second, using different colors for the points corresponding to the three species would help.

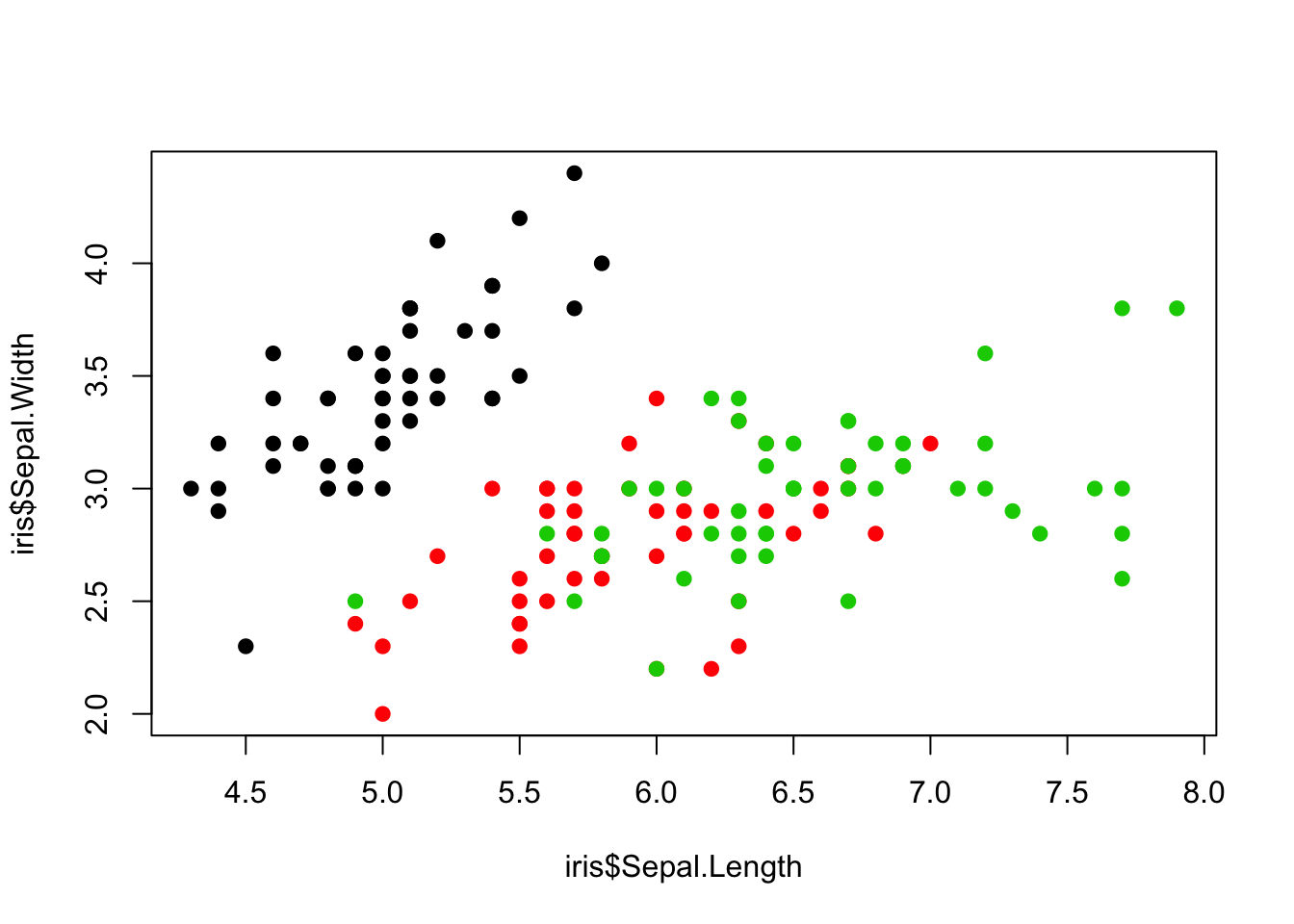

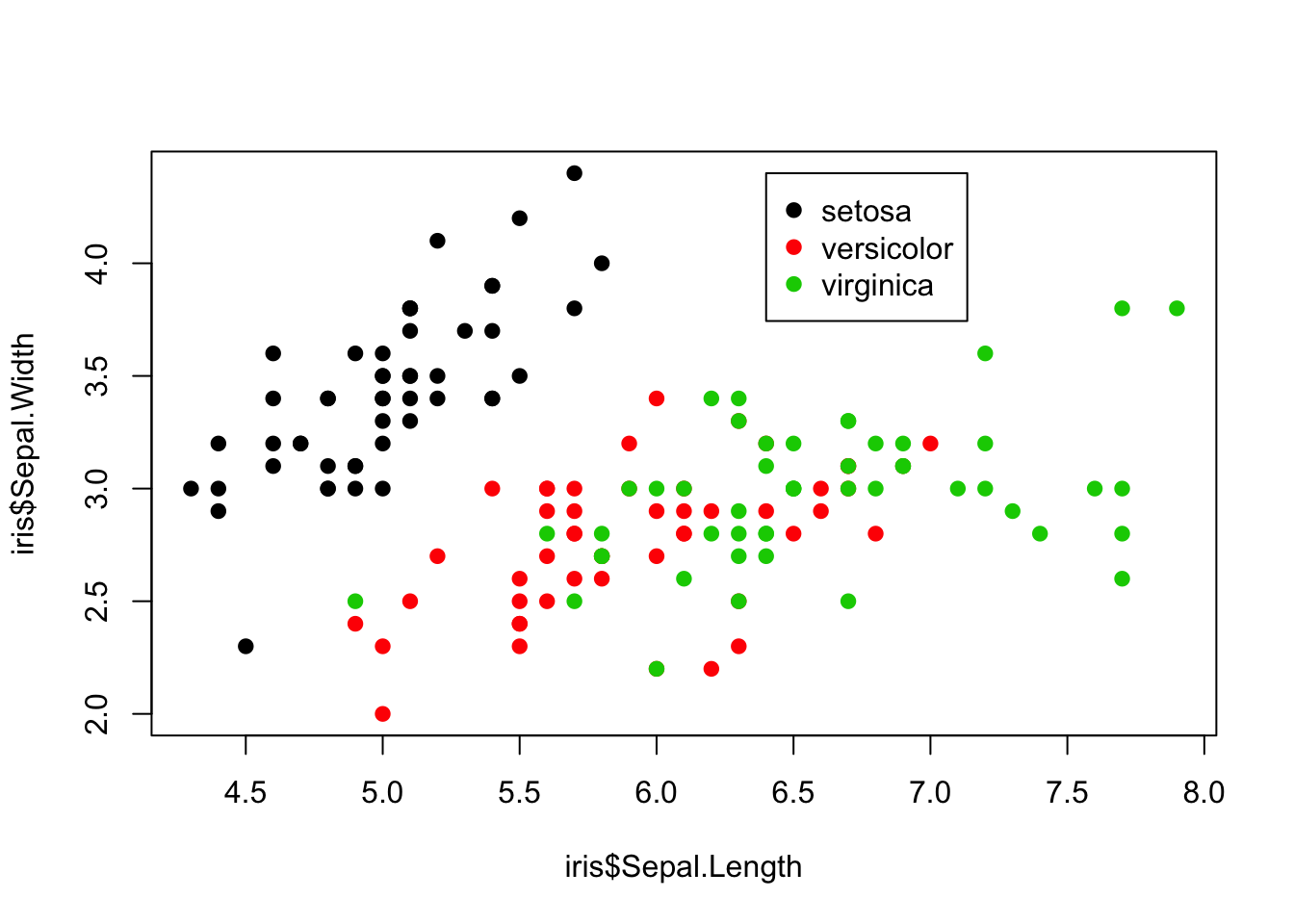

The pch = argument is used to control the type of symbol used to represent the data points. pch = 19 specifies a filled in circle for each data point. You can mess around with different numbers and you’ll see a wide variety of options. The col = iris$Species argument tells the plot() function to assign a different color to each unique value in the the iris$Species vector.45 Notice however that there is no legend produced by default, so we don’t know which color represents each species. We can add a legend using the legend() function.

> plot(x = iris$Sepal.Length, y = iris$Sepal.Width, pch = 19,

+ col = iris$Species)

> legend(x = 6.4, y = 4.4, legend = levels(iris$Species),

+ col = 1:length(levels(iris$Species)), pch = 19)

Let’s walk through the additional complexities one at a time:

x = 6.4, y = 4.4specifies the location where the legend is drawn. Here I place it in a location where the box will not cover up any data points.legend = levels(iris$Species)specifies the names of the different categories that will appear in the legend.col = 1:length(levels(iris$Species))specifies the number of colors that are represented in the function. In this case, we uselength(levels(iris$Species))to get the number of unique species in the data set, which turns out to be 3.pch = 19specifies the type of symbol to include in the legend.

It may seem like there are a lot of arguments to specify to produce a legend and a simple scatter plot, but this also means we have a lot of control over the graph, which is very useful when you are trying to develop a publication-quality figure for your own work.

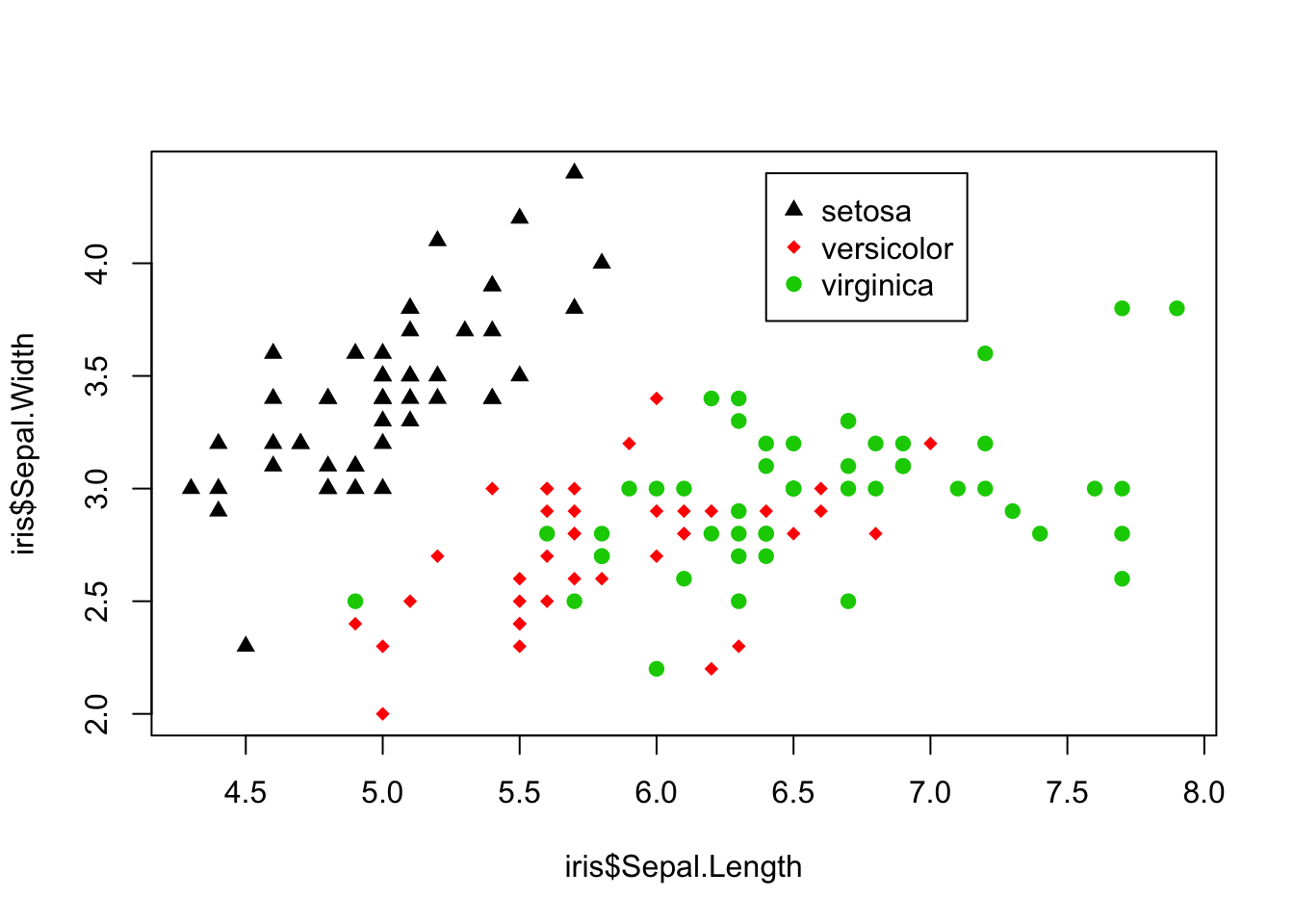

Now perhaps we want to use different shapes as well for the different species. To do this we assign different values for the pch argument to each species, and subsequently change the pch argument in the legend as well.

> plot(x = iris$Sepal.Length, y = iris$Sepal.Width, pch = c(17,

+ 18, 19)[iris$Species], col = iris$Species)

> legend(x = 6.4, y = 4.4, legend = levels(iris$Species),

+ col = 1:length(levels(iris$Species)), pch = c(17, 18,

+ 19))

11.1.1 Adding lines to a scatter plot

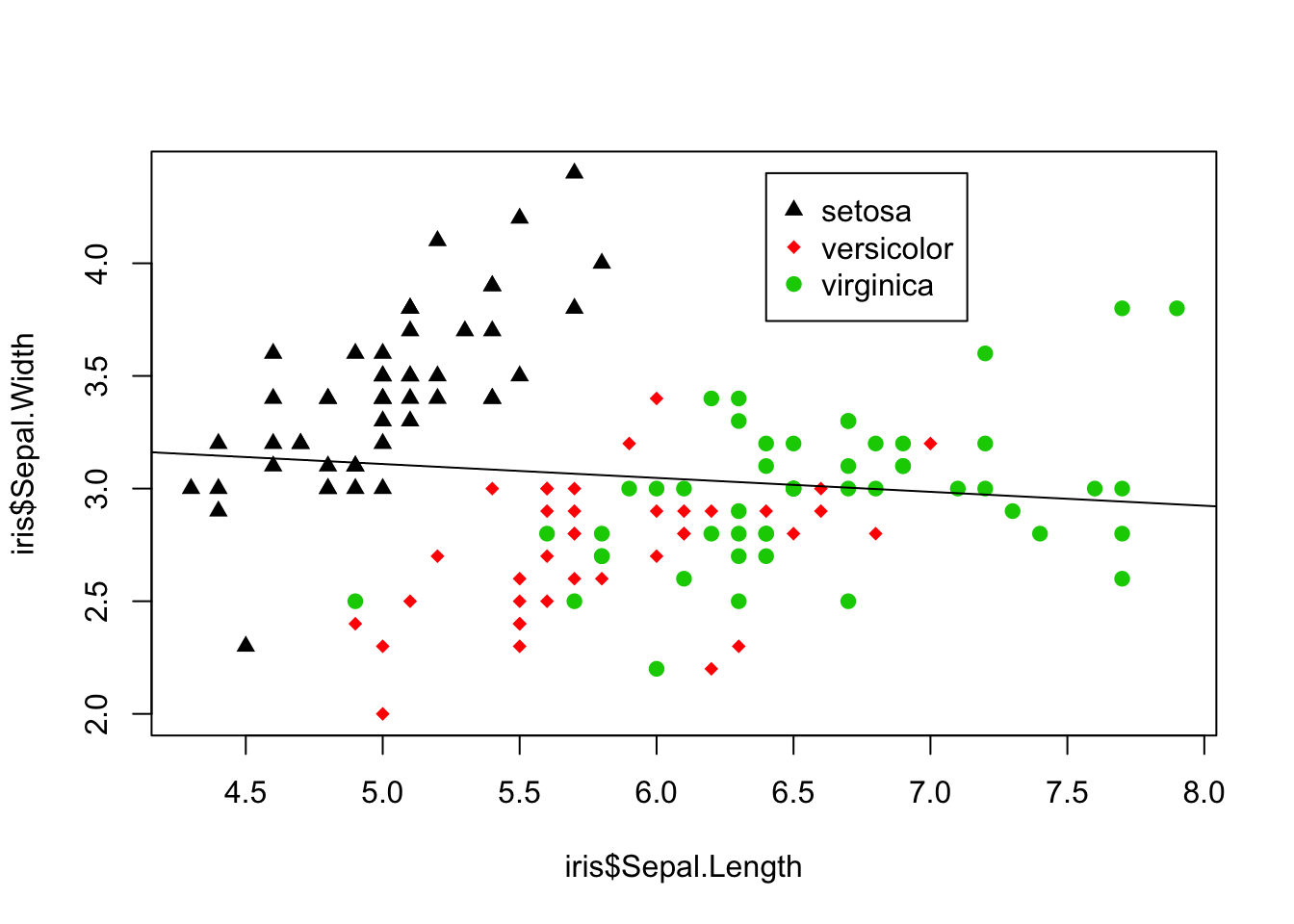

Next let’s add a fitted least squares line to the scatter plot. This can be done pretty easily using the abline() function to add a straight ine to the curve, and the lm() function to actually compute the least squares line

> plot(x = iris$Sepal.Length, y = iris$Sepal.Width, pch = c(17,

+ 18, 19)[iris$Species], col = iris$Species)

> legend(x = 6.4, y = 4.4, legend = levels(iris$Species),

+ col = 1:length(levels(iris$Species)), pch = c(17, 18,

+ 19))

> abline(lm(iris$Sepal.Width ~ iris$Sepal.Length))

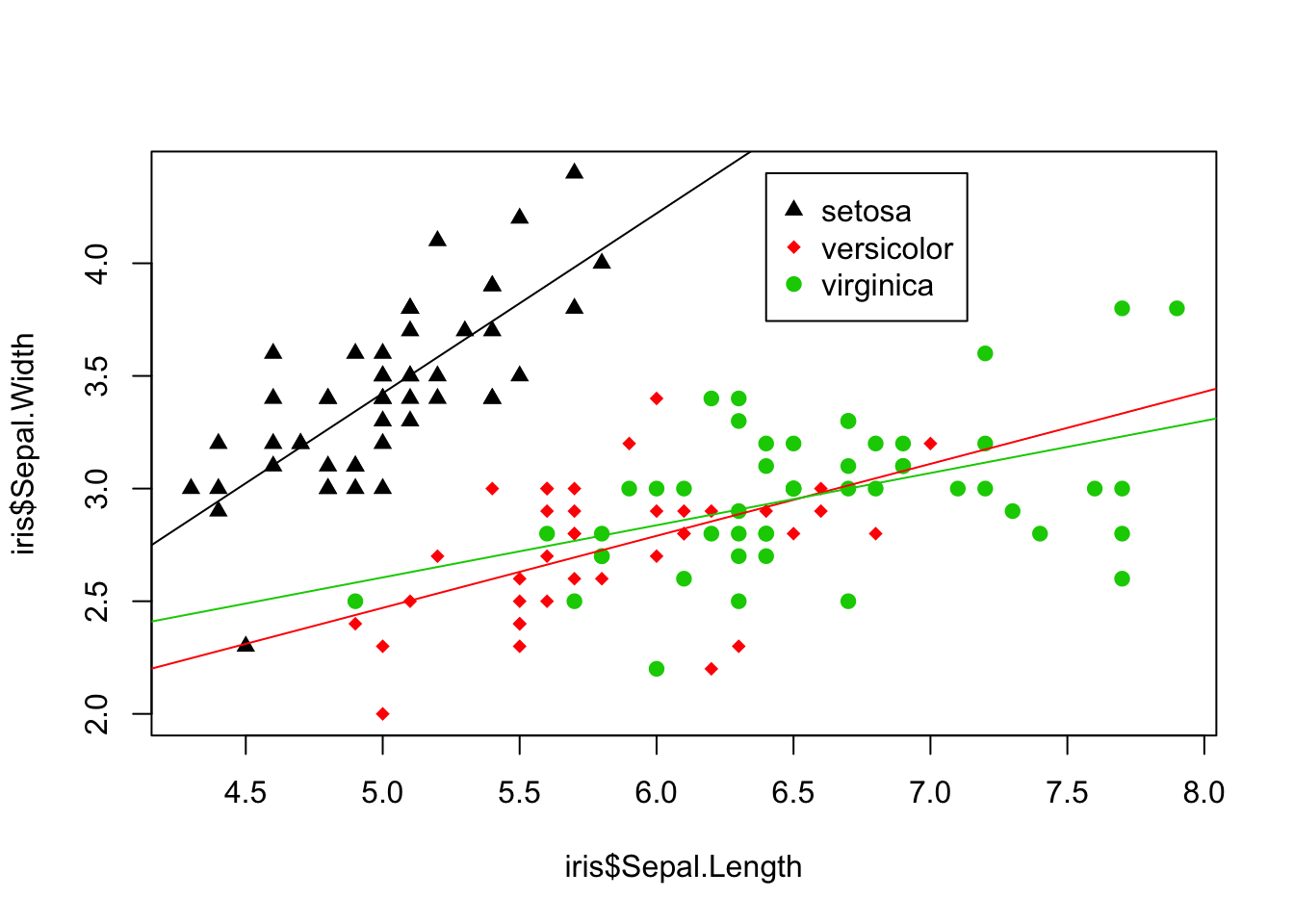

For the iris data, it probably makes more sense to fit separate lines by species. Below we compute the linear model separately for each species, then use the abline() function to add each line to the graph. Note our use of logical subsetting to obtain separate data frames for each species.

> iris.setosa <- iris[iris$Species == "setosa", ]

> iris.versicolor <- iris[iris$Species == "versicolor", ]

> iris.virginica <- iris[iris$Species == "virginica", ]

> plot(x = iris$Sepal.Length, y = iris$Sepal.Width, pch = c(17,

+ 18, 19)[iris$Species], col = iris$Species)

> legend(x = 6.4, y = 4.4, legend = levels(iris$Species),

+ col = 1:length(levels(iris$Species)), pch = c(17, 18,

+ 19))

> abline(lm(iris.setosa$Sepal.Width ~ iris.setosa$Sepal.Length),

+ col = 1)

> abline(lm(iris.versicolor$Sepal.Width ~ iris.versicolor$Sepal.Length),

+ col = 2)

> abline(lm(iris.virginica$Sepal.Width ~ iris.virginica$Sepal.Length),

+ col = 3)

Note that we could also do this using a for loop, which you will learn about soon in Chapter 7.

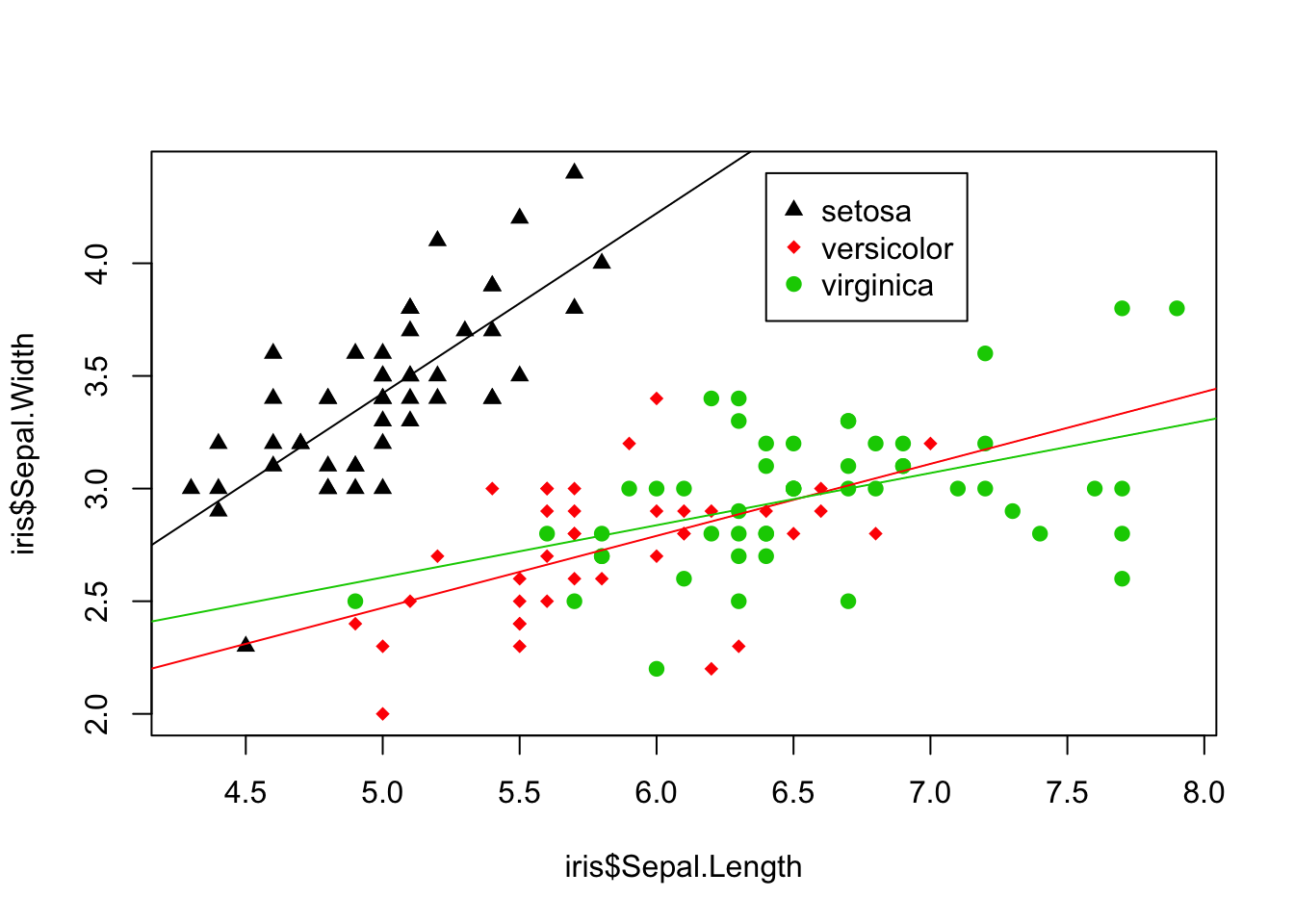

> iris.setosa <- iris[iris$Species == "setosa", ]

> iris.versicolor <- iris[iris$Species == "versicolor", ]

> iris.virginica <- iris[iris$Species == "virginica", ]

> plot(x = iris$Sepal.Length, y = iris$Sepal.Width, pch = c(17,

+ 18, 19)[iris$Species], col = iris$Species)

> legend(x = 6.4, y = 4.4, legend = levels(iris$Species),

+ col = 1:length(levels(iris$Species)), pch = c(17, 18,

+ 19))

> for (i in 1:length(levels(iris$Species))) {

+ curr.species <- iris[iris$Species == levels(iris$Species)[i],

+ ]

+ abline(lm(curr.species$Sepal.Width ~ curr.species$Sepal.Length),

+ col = i)

+ }

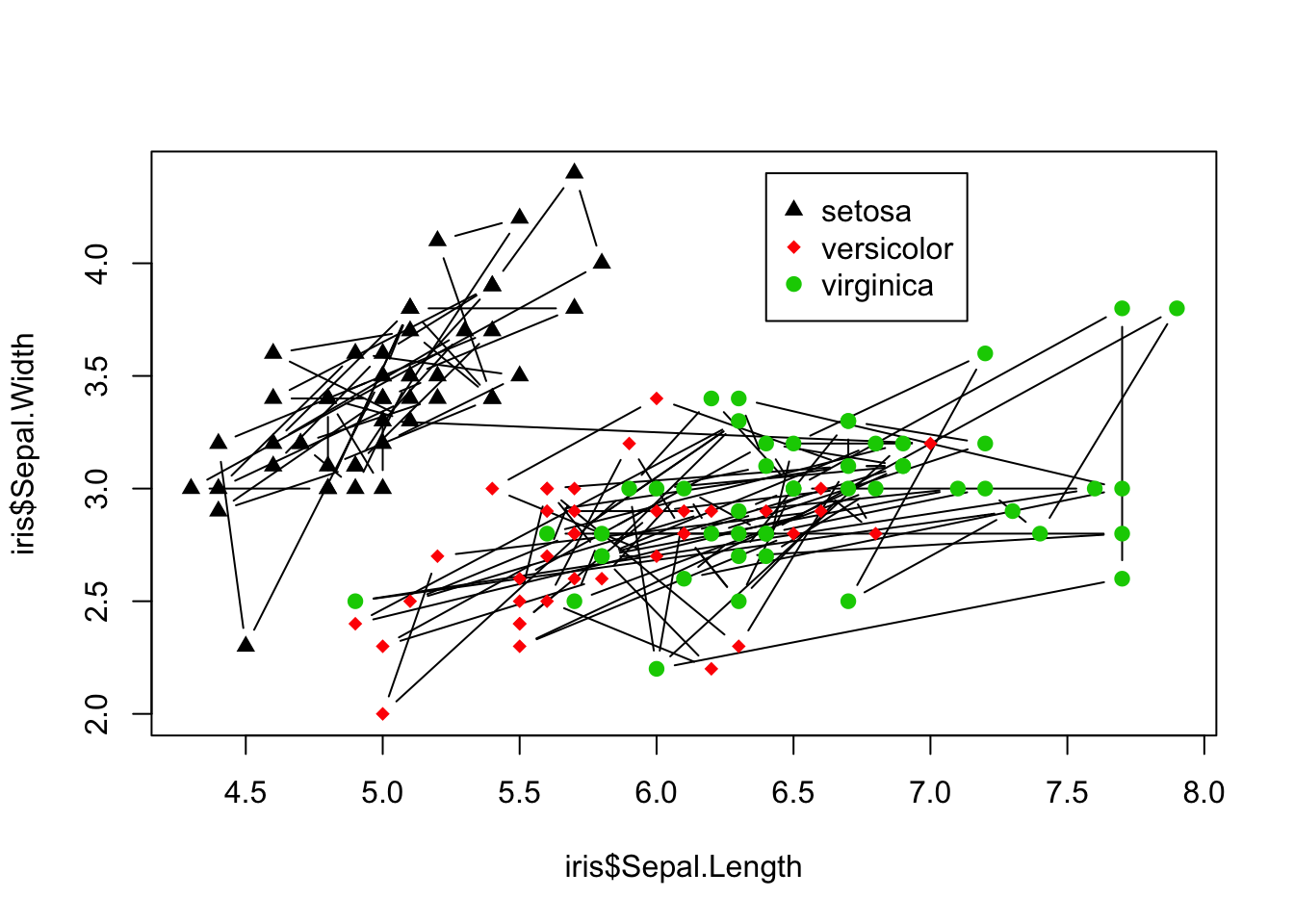

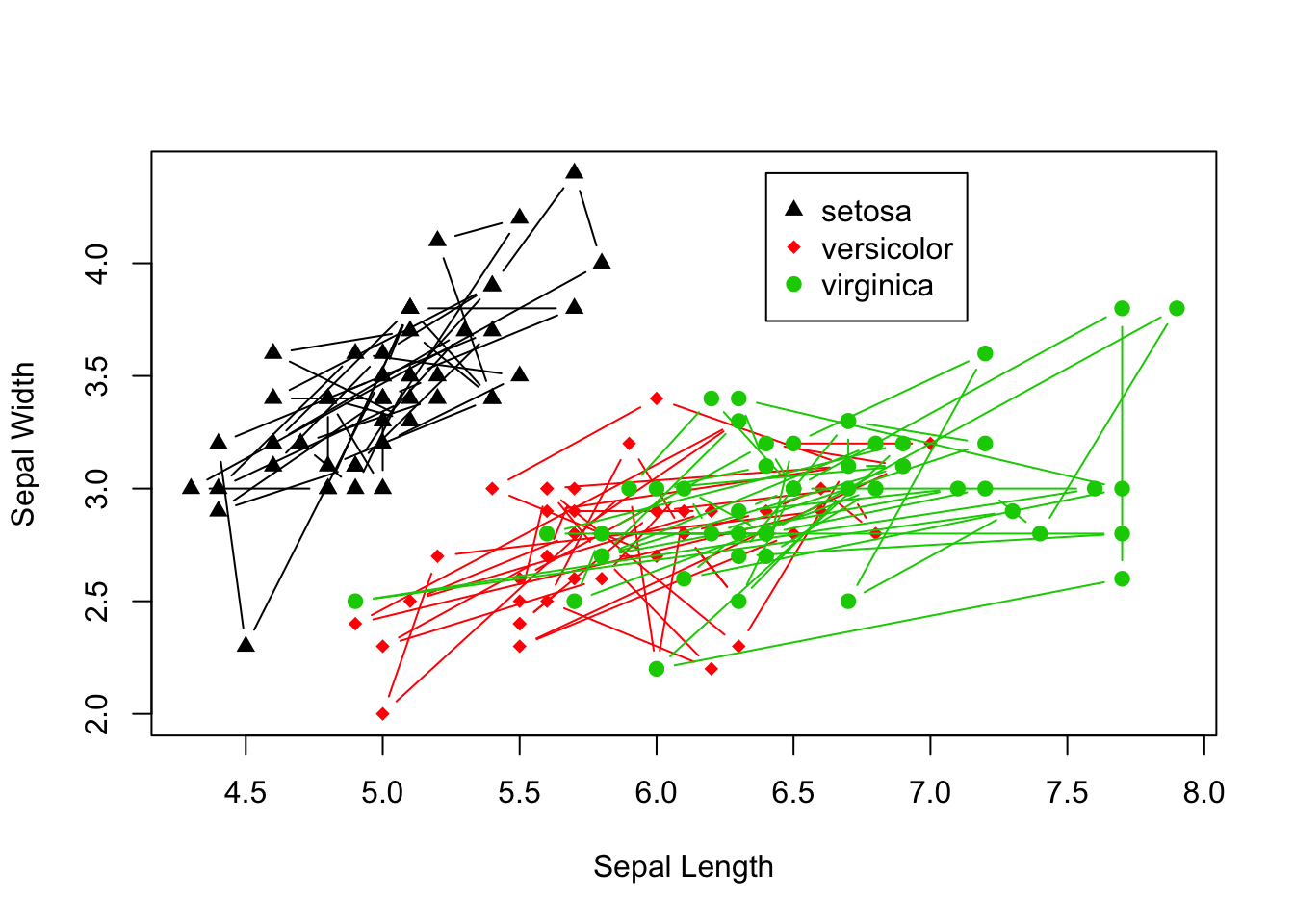

Another common use of line segments in a graphic is to connect the points in order. Although it is not clear why this helps in understanding the iris data, the technique is illustrated next. First we connect all lines regardless of species. This is done easily by specifying the argument type = 'b' in the plot() function46

> plot(x = iris$Sepal.Length, y = iris$Sepal.Width, pch = c(17,

+ 18, 19)[iris$Species], col = iris$Species, type = "b")

> legend(x = 6.4, y = 4.4, legend = levels(iris$Species),

+ col = 1:length(levels(iris$Species)), pch = c(17, 18,

+ 19))

Now we attempt to only connect the points within a given species. Doing this requires the use of the lines() function to draw three separate lines for each species47 First we create a plot for the first species, and then subsequently use the lines() function to add each of the remaining two species to the plot. Notice that there are some additional arguments in the original plot() function that we have yet to cover. Don’t worry, we’ll talk about all this fun stuff in the next section :)

> plot(x = iris$Sepal.Length[iris$Species == "setosa"], y = iris$Sepal.Width[iris$Species ==

+ "setosa"], pch = 17, col = 1, type = "b", xlim = range(iris$Sepal.Length),

+ ylim = range(iris$Sepal.Width), xlab = "Sepal Length",

+ ylab = "Sepal Width")

> lines(x = iris$Sepal.Length[iris$Species == "versicolor"],

+ y = iris$Sepal.Width[iris$Species == "versicolor"],

+ pch = 18, col = 2, type = "b")

> lines(x = iris$Sepal.Length[iris$Species == "virginica"],

+ y = iris$Sepal.Width[iris$Species == "virginica"], pch = 19,

+ col = 3, type = "b")

> legend(x = 6.4, y = 4.4, legend = levels(iris$Species),

+ col = 1:length(levels(iris$Species)), pch = c(17, 18,

+ 19))

11.2 Labels, Axes, Text, etc.

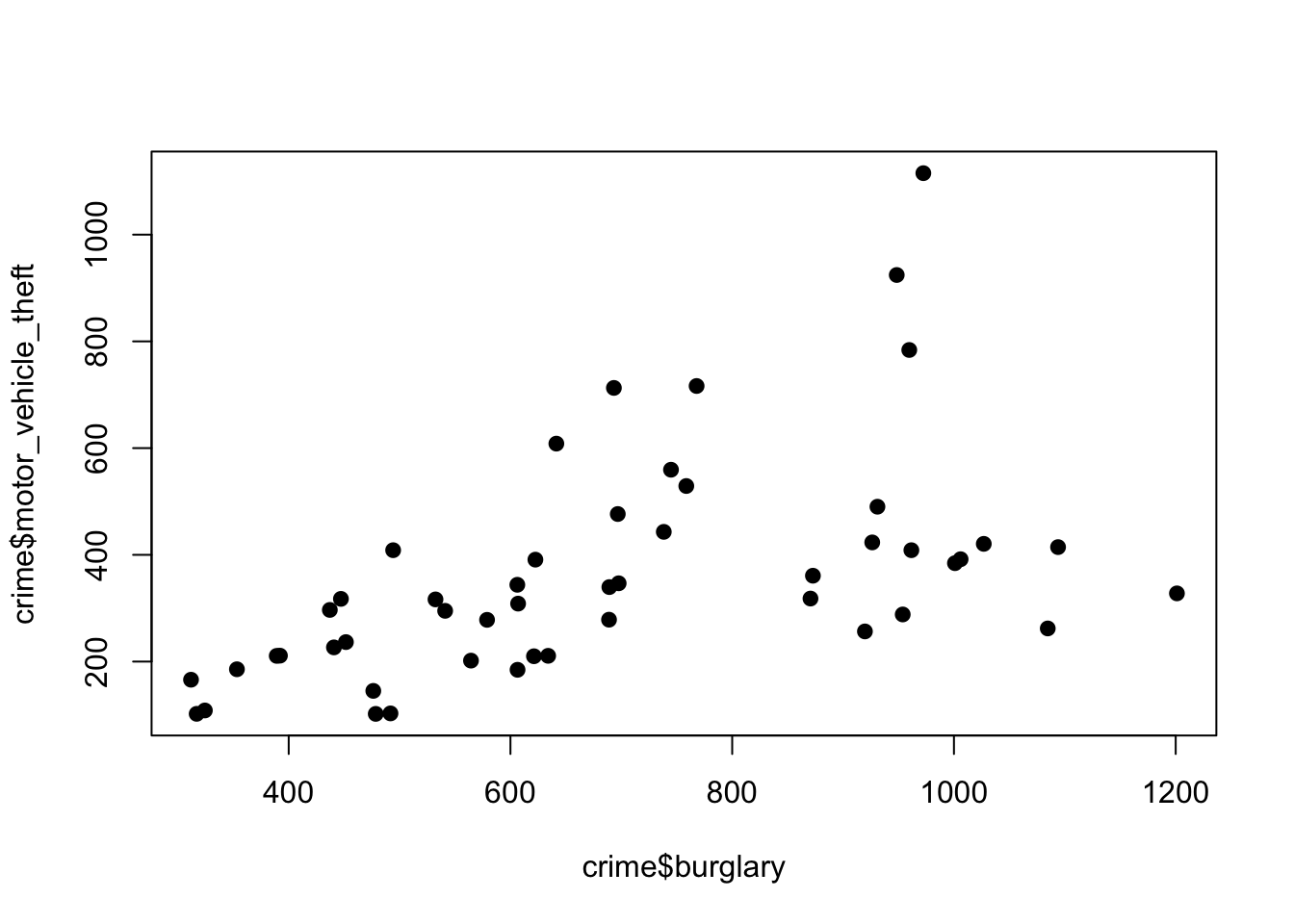

The default settings of graphics often produce useful graphics, but once a graphic is chosen for dissemination, the user will likely want to customize things like the title, axes, etc. In this section some tools for customization are presented. Most will be illustrated in the context of a data set on crime rates in the 50 states in the United States. These data were made available by Nathan Yau at http://flowingdata.com/2010/11/23/how-to-make-bubble-charts/. The data include crime rates per 100,000 people for various crimes such as murder and robbery, and also include each state’s population. The crime rates are from the year 2005, while the population numbers are from the year 2008, but the difference in population between the years is not great, and the exact population is not particularly important for what we’ll do below.

First, read in the data, examine its structure, and produce a simple scatter plot of motor vehicle theft versus burglary.

> u.crime <- "https://www.finley-lab.com/files/data/crimeRatesByState2005.csv"

> crime <- read.csv(u.crime, header=TRUE)

> str(crime)'data.frame': 50 obs. of 9 variables:

$ state : Factor w/ 50 levels "Alabama ","Alaska ",..: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 ...

$ murder : num 8.2 4.8 7.5 6.7 6.9 3.7 2.9 4.4 5 6.2 ...

$ Forcible_rate : num 34.3 81.1 33.8 42.9 26 43.4 20 44.7 37.1 23.6 ...

$ Robbery : num 141.4 80.9 144.4 91.1 176.1 ...

$ aggravated_assult : num 248 465 327 387 317 ...

$ burglary : num 954 622 948 1085 693 ...

$ larceny_theft : num 2650 2599 2965 2711 1916 ...

$ motor_vehicle_theft: num 288 391 924 262 713 ...

$ population : int 4627851 686293 6500180 2855390 36756666 4861515 3501252 873092 18328340 9685744 ...

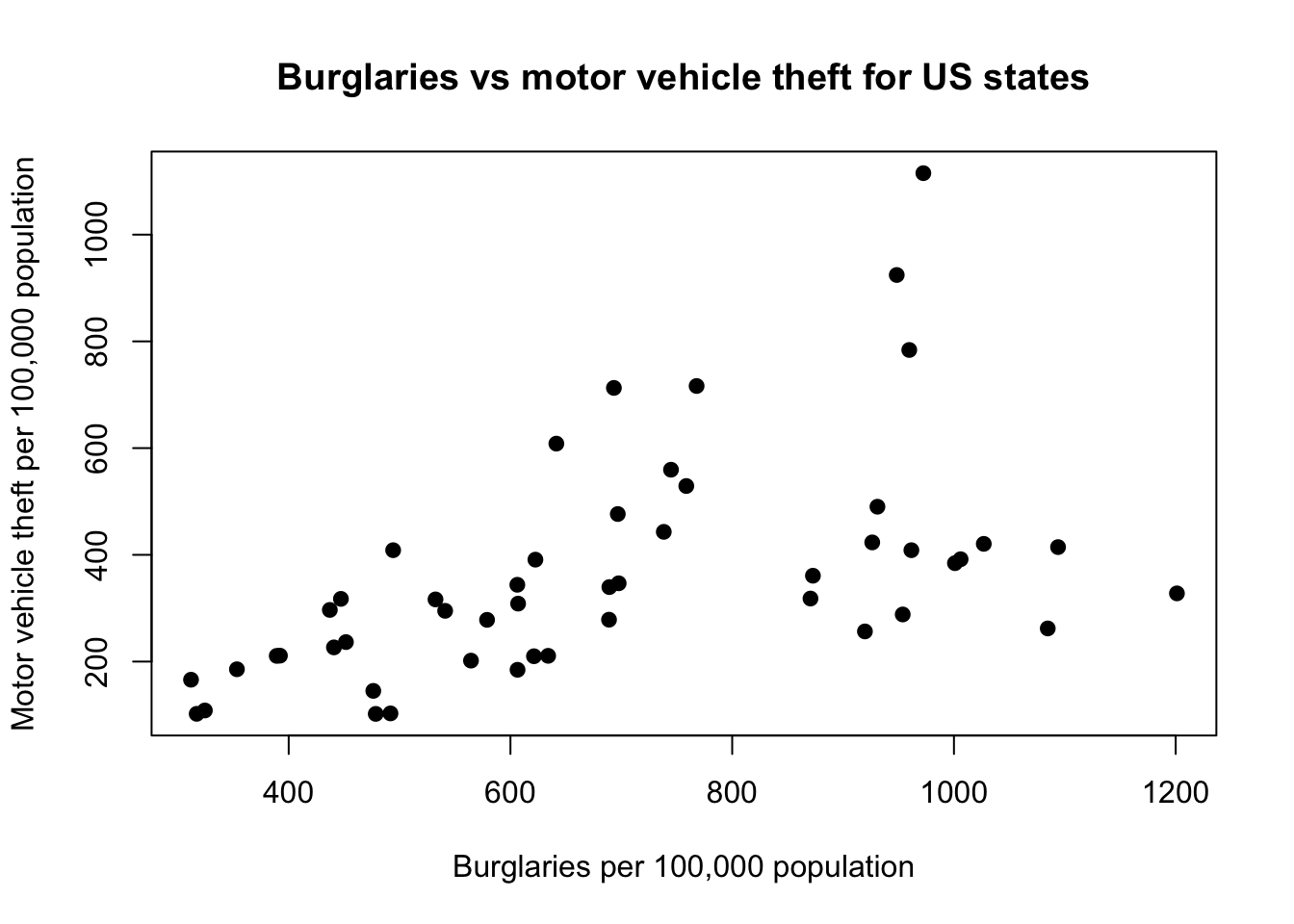

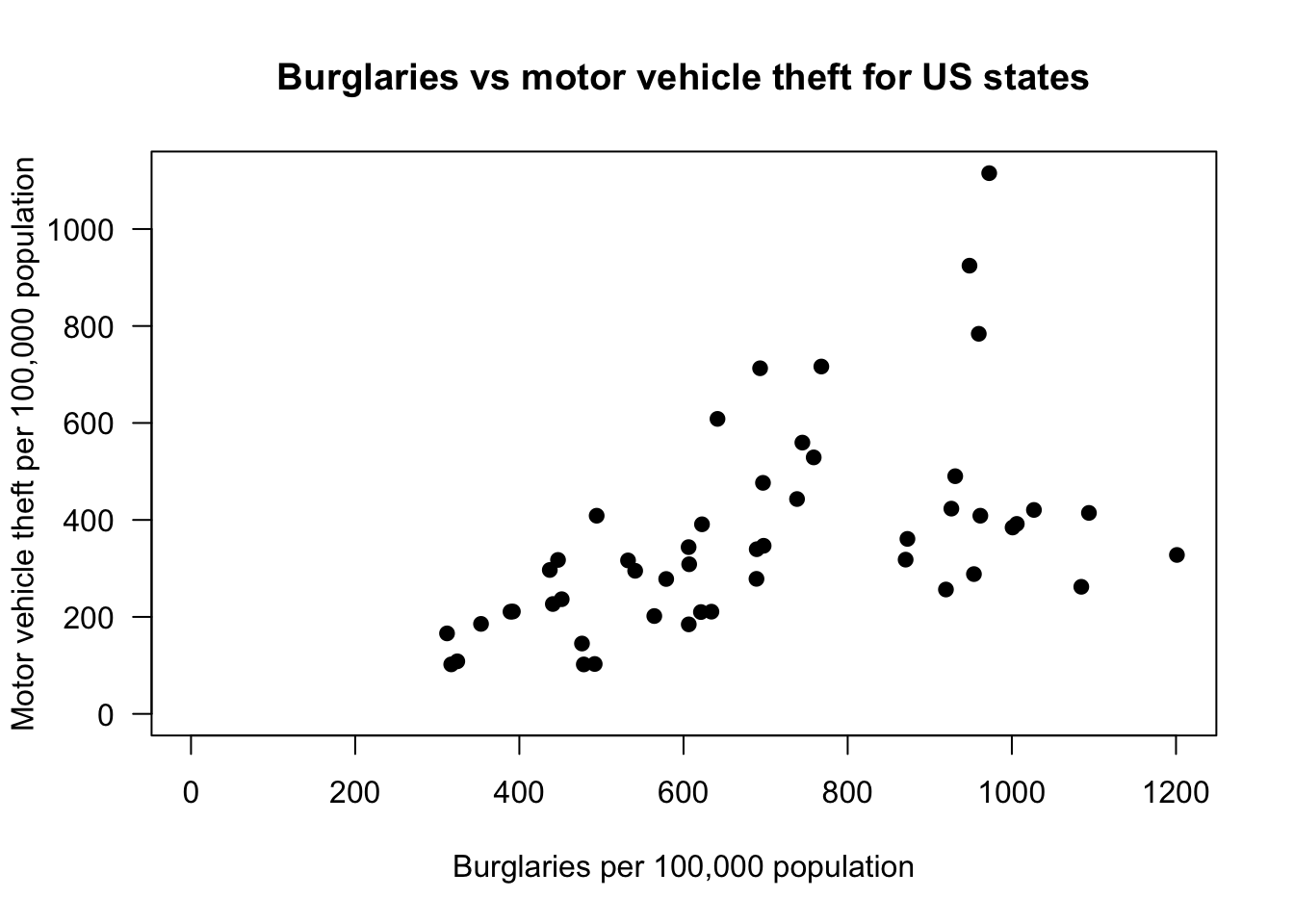

11.2.1 Labels

By default, axis labels are the values of the x and y values you supply to the plot() function. For making a publication-quality figure, we often want to further customize these labels, as well as potentially add a title to the graph. We can do this using the xlab, ylab, and main arguments in the plot() function.

> plot(crime$burglary, crime$motor_vehicle_theft, pch = 19,

+ xlab = "Burglaries per 100,000 population", ylab = "Motor vehicle theft per 100,000 population",

+ main = "Burglaries vs motor vehicle theft for US states")

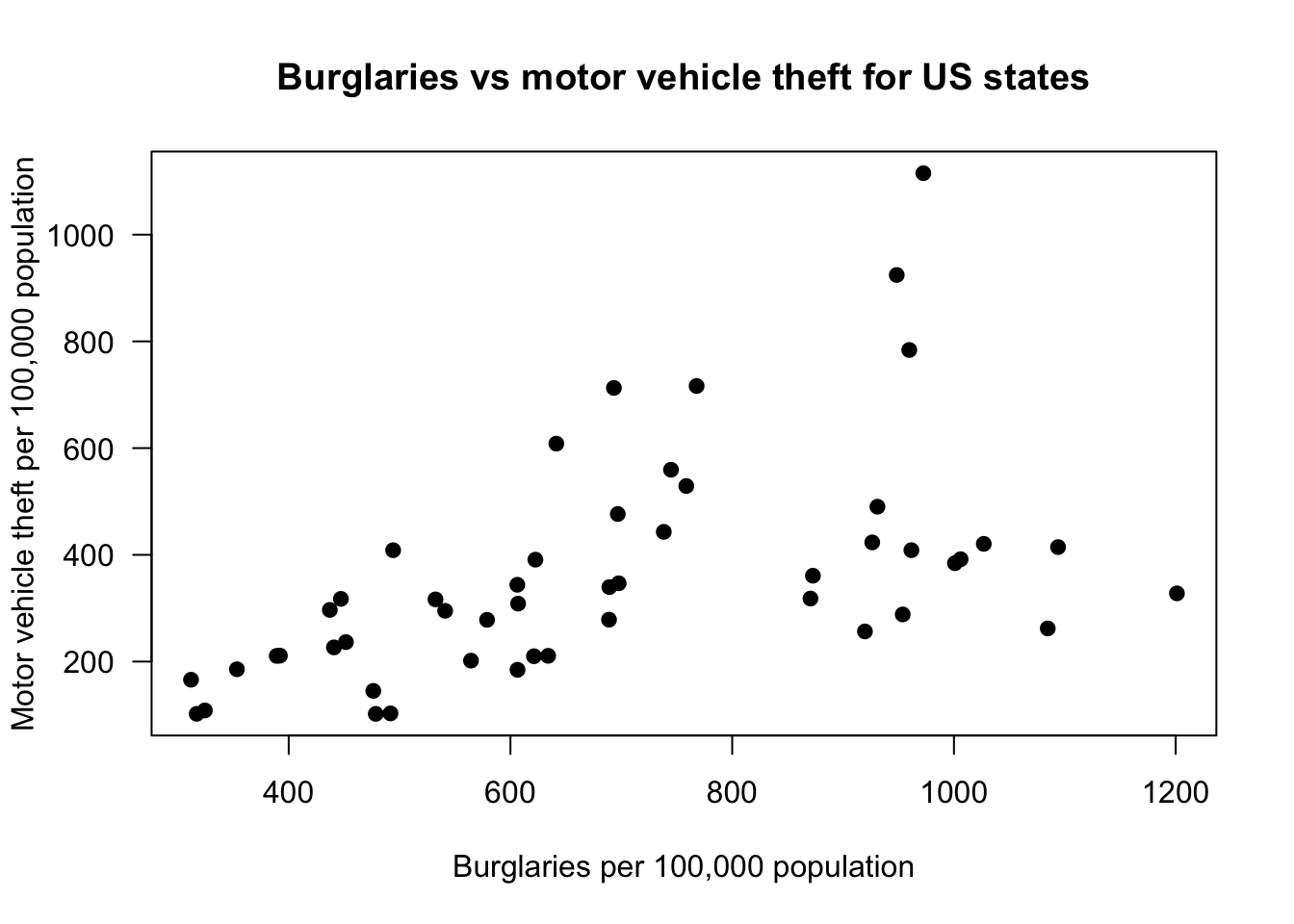

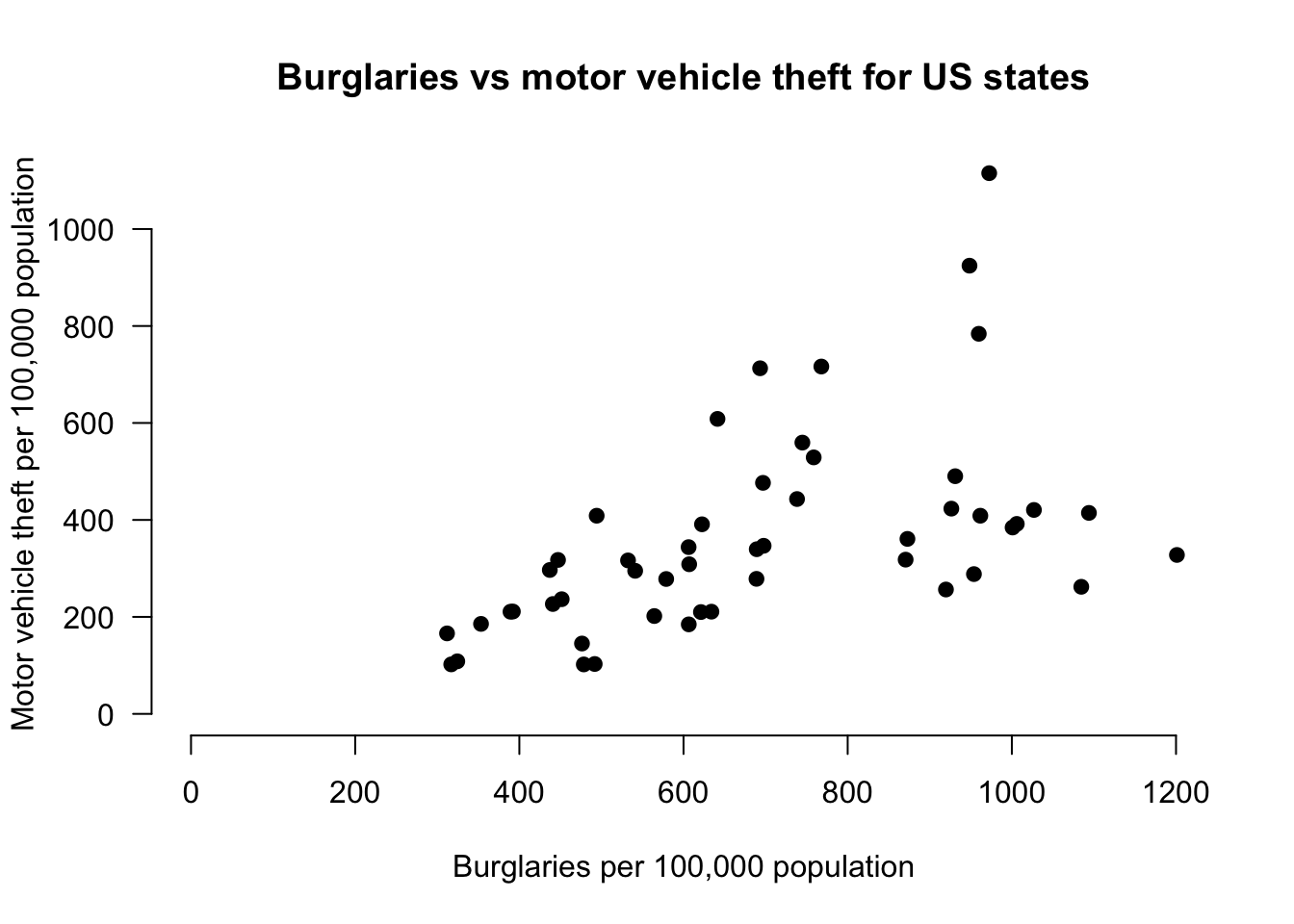

Perhaps it may be easier to read the values on the y-axis if they were oritented horizontally instead of vertically. We can do this using the las = 1 argument.

> plot(crime$burglary, crime$motor_vehicle_theft, pch = 19,

+ xlab = "Burglaries per 100,000 population", ylab = "Motor vehicle theft per 100,000 population",

+ main = "Burglaries vs motor vehicle theft for US states",

+ las = 1)

11.3 Customizing Axes

The basic plot() function provides defaults for the axis limits, as well as for other axis features (i.e., the box around the plot). These, and other axis features such as tick marks, labels, and transformations, can all be customized. First, we use the xlim and ylim arguments to make the x and y axes start at zero and go to the maxium x and y values.

> plot(crime$burglary, crime$motor_vehicle_theft, pch = 19,

+ xlab = "Burglaries per 100,000 population", ylab = "Motor vehicle theft per 100,000 population",

+ main = "Burglaries vs motor vehicle theft for US states",

+ las = 1, xlim = c(0, max(crime$burglary)), ylim = c(0,

+ max(crime$motor_vehicle_theft)))

Now we eliminate the axes and box automatically drawn by the plot() function, and subsequently add our own axes using the axis() function. We use most of the defaults provided by the axis() function, however, looking at the help page for axis() reveals a large amount of possibilities for customizing the axes in whatever way you desire.

> plot(crime$burglary, crime$motor_vehicle_theft, pch = 19,

+ xlab = "Burglaries per 100,000 population", ylab = "Motor vehicle theft per 100,000 population",

+ main = "Burglaries vs motor vehicle theft for US states",

+ las = 1, axes = FALSE, xlim = c(0, max(crime$burglary)),

+ ylim = c(0, max(crime$motor_vehicle_theft)))

> axis(side = 1)

> axis(side = 2, las = 1)

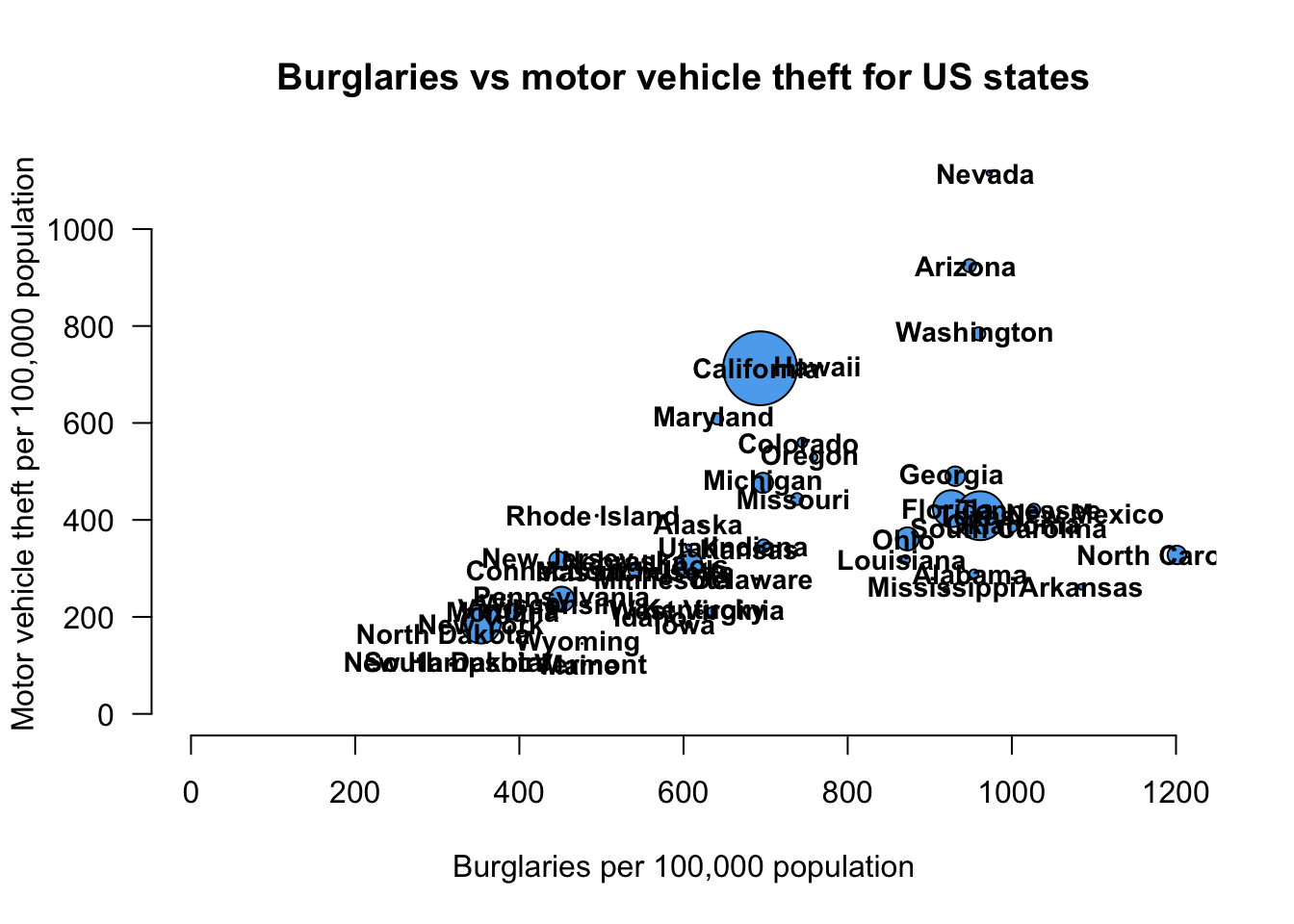

11.3.1 Text, Point Size, and Color

Next we make point size proportional to population, change the color, and add a state label. First we make point size proportional to population size using the symbols() function. We can control the color of the points using the bg argument in the symbols() function. We then use the text() function to add labels to each point.

> symbols(crime$burglary, crime$motor_vehicle_theft, pch = 19,

+ xlab = "Burglaries per 100,000 population", ylab = "Motor vehicle theft per 100,000 population",

+ main = "Burglaries vs motor vehicle theft for US states",

+ las = 1, xlim = c(0, max(crime$burglary)), ylim = c(0,

+ max(crime$motor_vehicle_theft)), circles = crime$population,

+ inches = 1/5, axes = FALSE, bg = "steelblue2")

> axis(side = 1)

> axis(side = 2, las = 1)

> text(crime$burglary, crime$motor_vehicle_theft, labels = crime$state,

+ cex = 0.9, font = 2)

This graph is mind-numbingly busy, and is missing some notable things (i.e. legend). For now, we leave it up to you to add in a legend, make the graph less cluttered, fix the cutoff labels, etc. if you so desire.

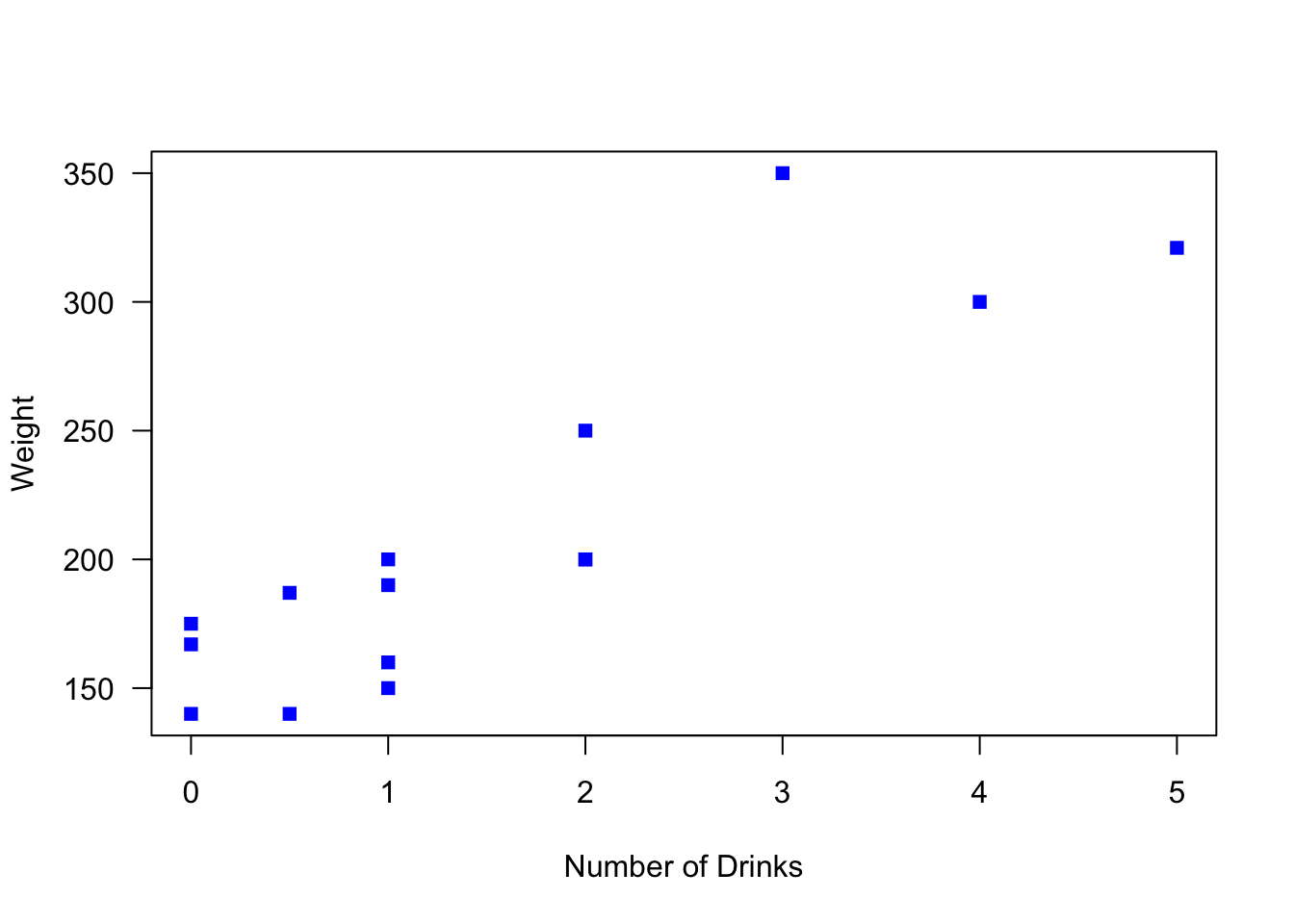

You run an experiment to see if the number of alcoholic beverages a person has on average every day is related to weight. You collect 15 data points. Enter these data in R by creating vectors, and then reproduce the following plot.

| # of Drinks | Weight |

|---|---|

| 1.0 | 150 |

| 3.0 | 350 |

| 2.0 | 200 |

| 0.5 | 140 |

| 2.0 | 200 |

| 1.0 | 160 |

| 0.0 | 175 |

| 0.0 | 140 |

| 0.0 | 167 |

| 1.0 | 200 |

| 4.0 | 300 |

| 5.0 | 321 |

| 2.0 | 250 |

| 0.5 | 187 |

| 1.0 | 190 |

11.4 Other Types of Graphics

Scatter and line plots, which have just been presented, are common but certainly not the only graphical displays in common use. Histograms, boxplots, and bar graphs, as well as more “mathematical” displays such as the graph of a function, are commonly used to represent data. Examples of each are presented below.

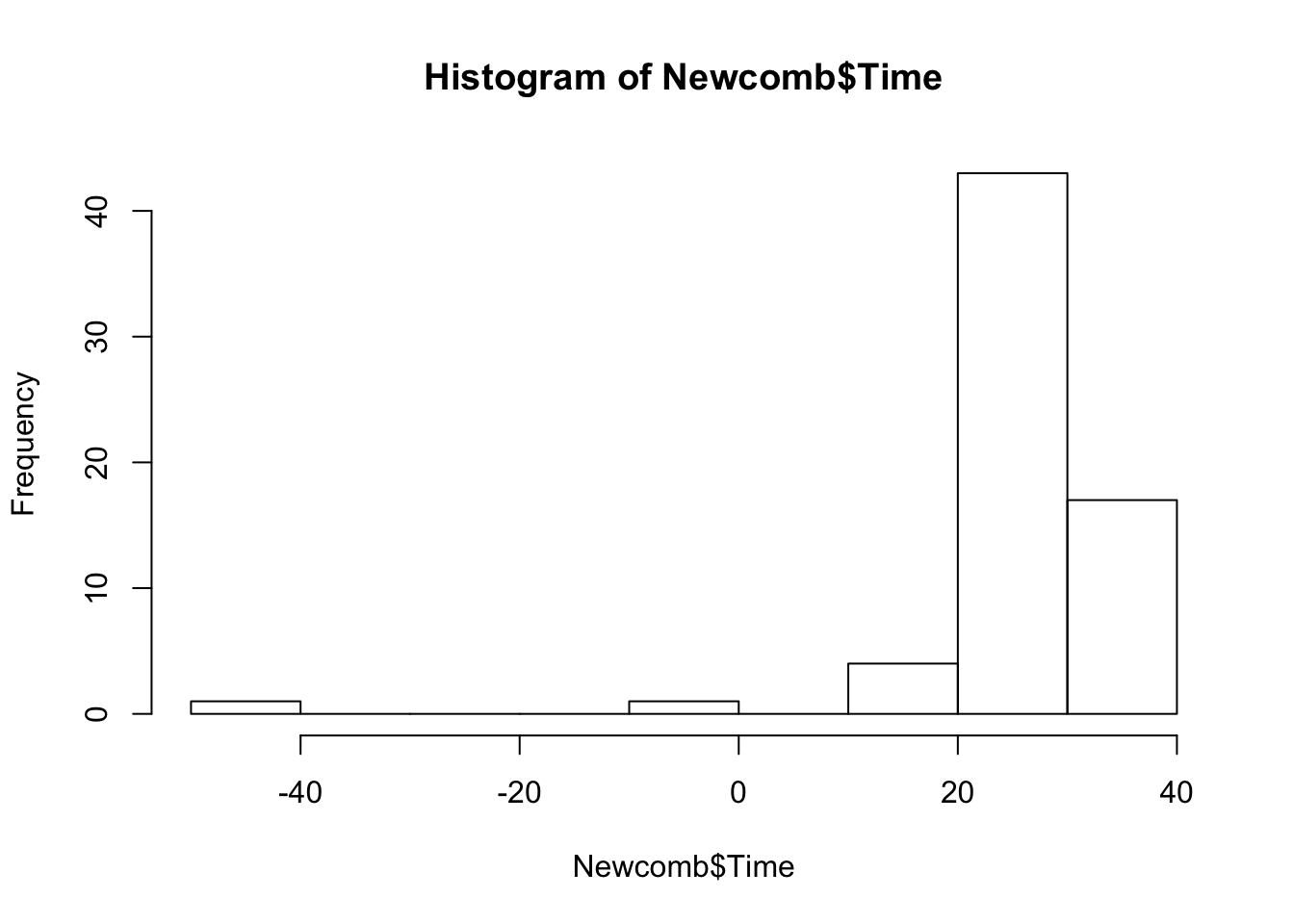

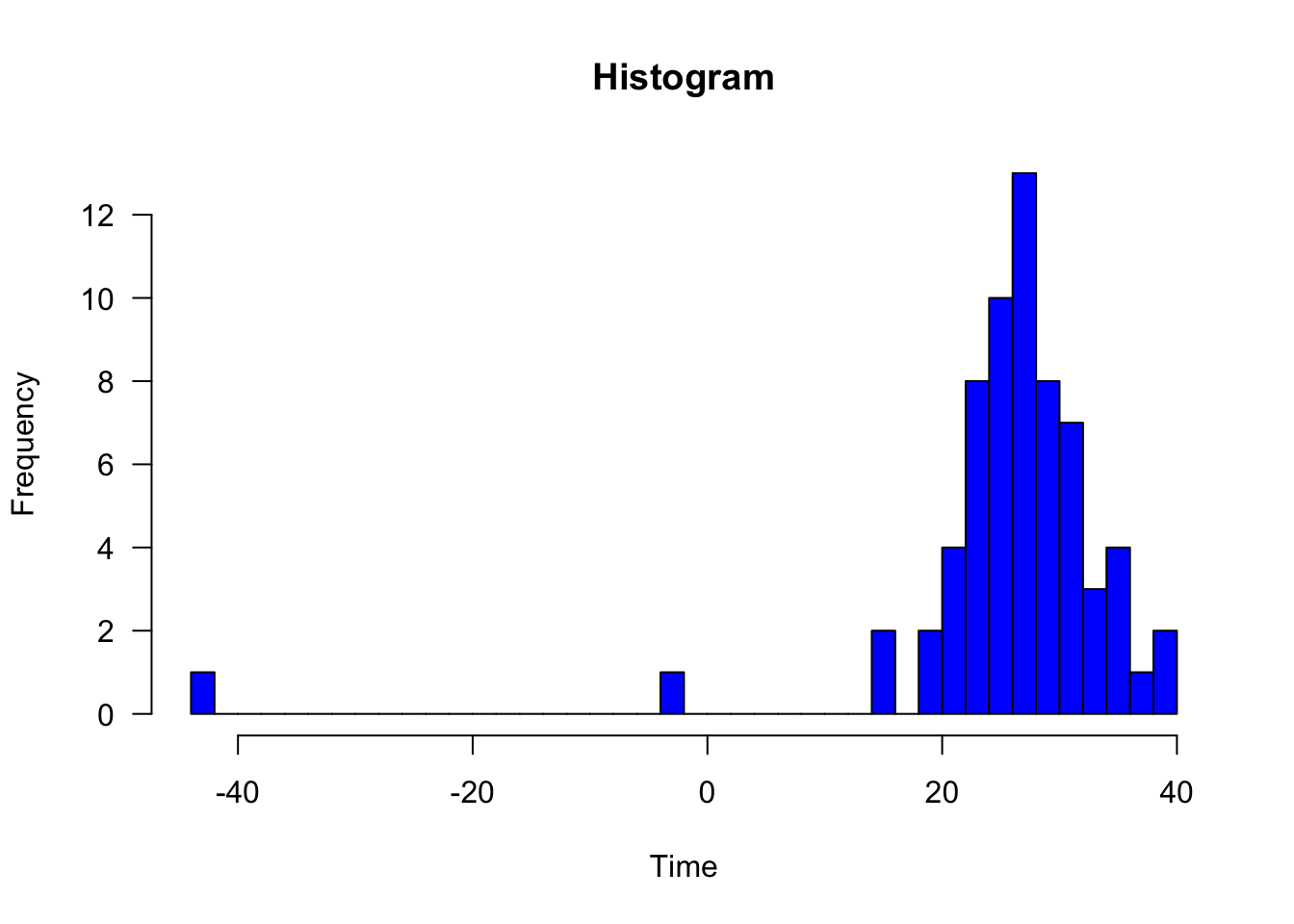

11.4.1 Histograms

Simon Newcomb conducted several experiments to estimate the speed of light by measuring the time it took for light to travel from his laboratory to a mirror at the base of the Washington Monument, and then back to his lab. This is a distance of \(7.44373\) km, and by dividing this distance by the measured time, an estimate for the speed of light is obtained.

The times are of course quite small, and to avoid working with very small numbers, the data are recoded to be the deviation from \(24800\) nanoseconds. For example an observation coded as \(28\) represents a time of \(24828\) nanoseconds, while an observation coded as \(-44\) represents a time of \(24756\) nanoseconds.

> u.newcomb <- "https://www.finley-lab.com/files/data/Newcomb.csv"

> Newcomb <- read.csv(u.newcomb, header = TRUE)

> head(Newcomb) Time

1 28

2 26

3 33

4 24

5 34

6 -44To produce a simple histogram of these data in the graphics package, we can use the simple hist() function.

The function automatically specifies the binwidths for the data, however we can easily change this ourselves to something more suitable using the breaks argument. We also change the axis labels, y-axis label orientation, title, and color of the bins.

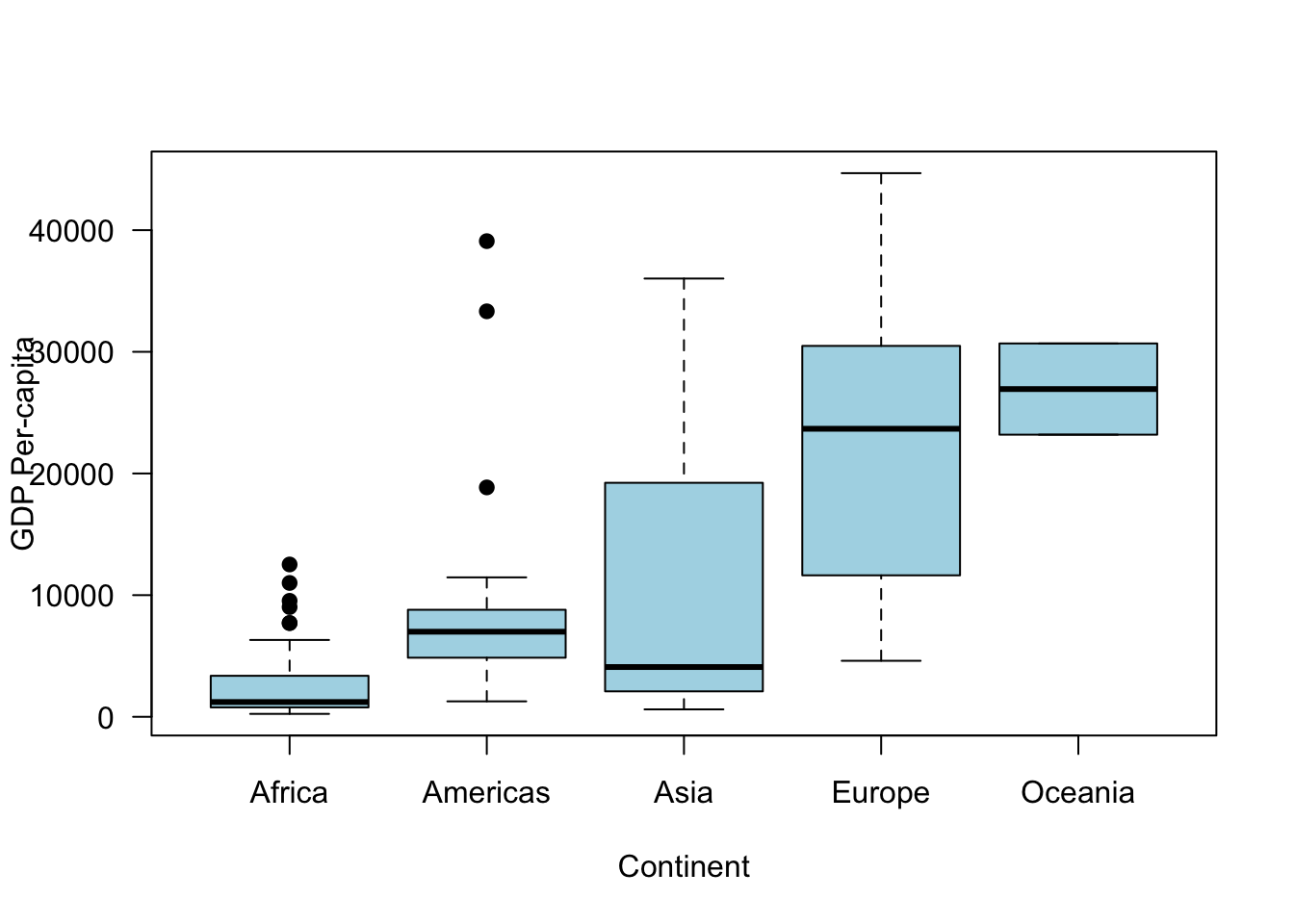

11.4.2 Boxplots

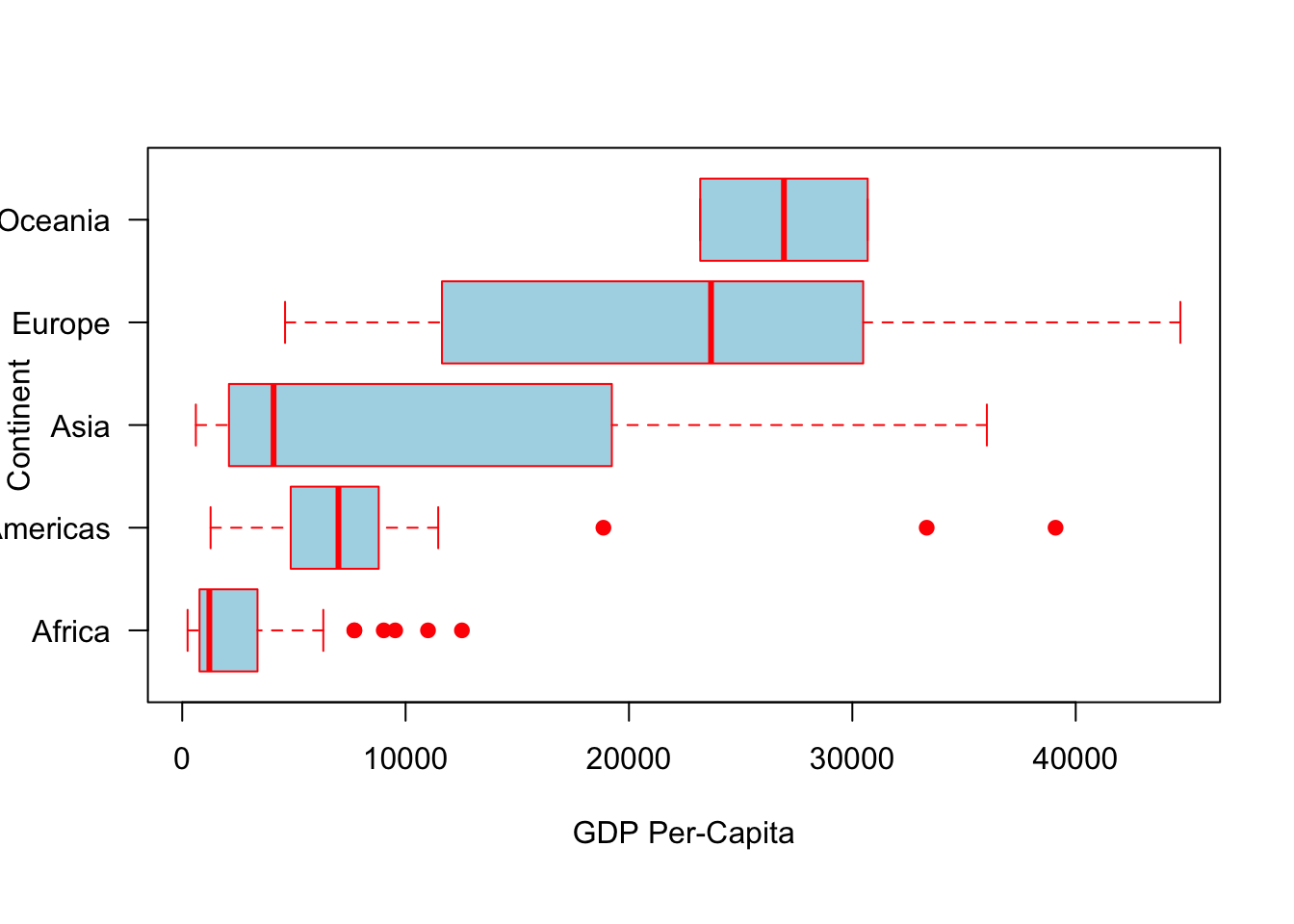

Next we consider some data from the gap minder data set to construct some box plots. These data are available in the gapminder package, which might need to be installed via install.packages("gapminder").

> library(gapminder)

> boxplot(gdpPercap ~ continent, data = subset(gapminder,

+ year == 2002), pch = 19, col = "lightblue", las = 1,

+ xlab = "Continent", ylab = "GDP Per-capita")

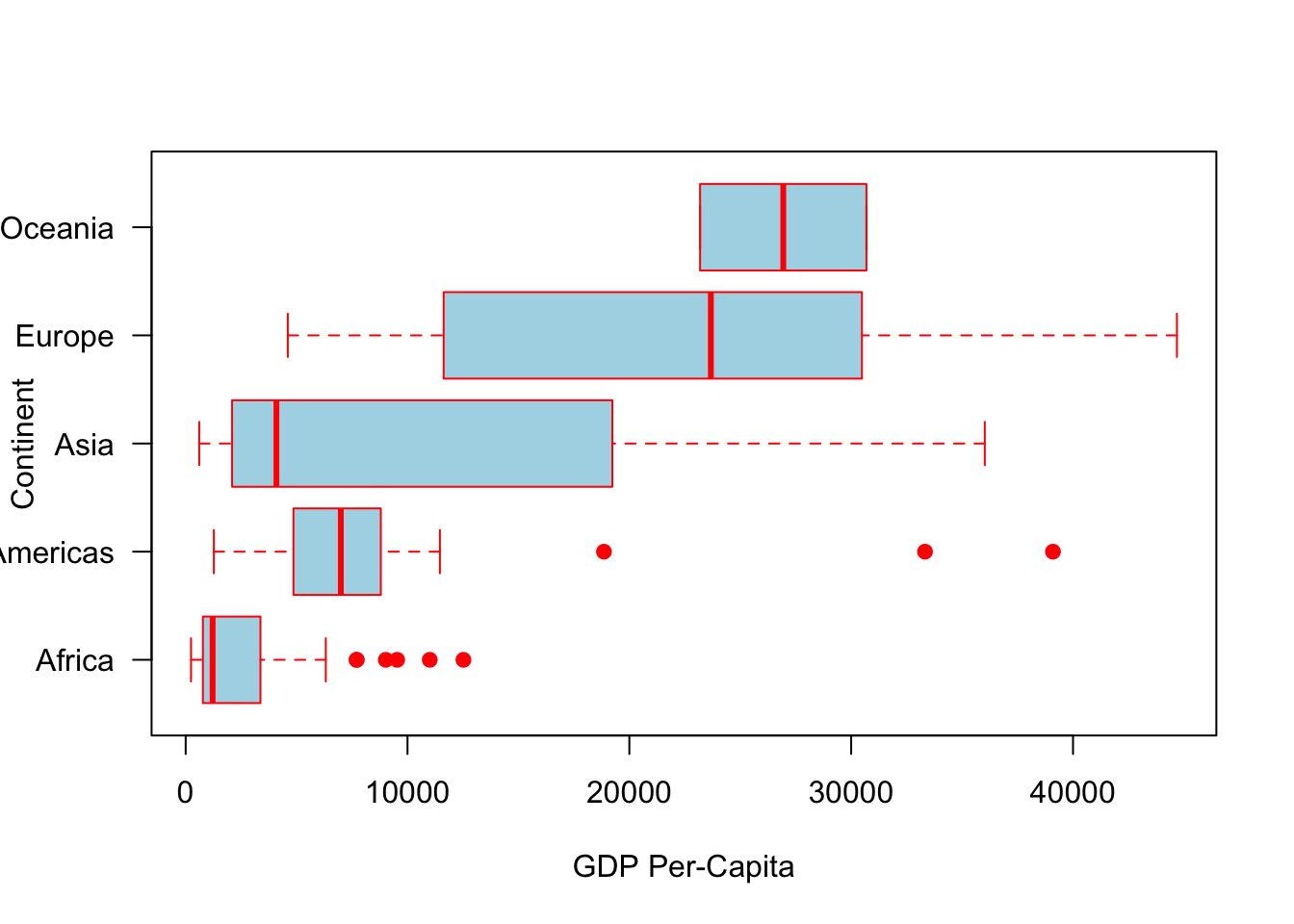

Here’s the same set of boxplots, but with different colors and the boxes plotted horizontally rather than vertically

> boxplot(gdpPercap ~ continent, data = subset(gapminder,

+ year == 2002), pch = 19, border = "red", col = "lightblue",

+ las = 1, xlab = "GDP Per-Capita", ylab = "Continent",

+ horizontal = TRUE)

However, notice in the last two graphs the y-axis labels were running off the page. Using the graphics package, we have the ability to adjust all the dimensions and parameters of a plot by using the par function. Below we utilize the par function to extend the amount of space in the plot on the left side of the graph.

> par(mar = c(6, 4, 4, 2))

> boxplot(gdpPercap ~ continent, data = subset(gapminder,

+ year == 2002), pch = 19, border = "red", col = "lightblue",

+ las = 1, xlab = "GDP Per-Capita", ylab = "Continent",

+ horizontal = TRUE)

11.4.3 Bar Graphs

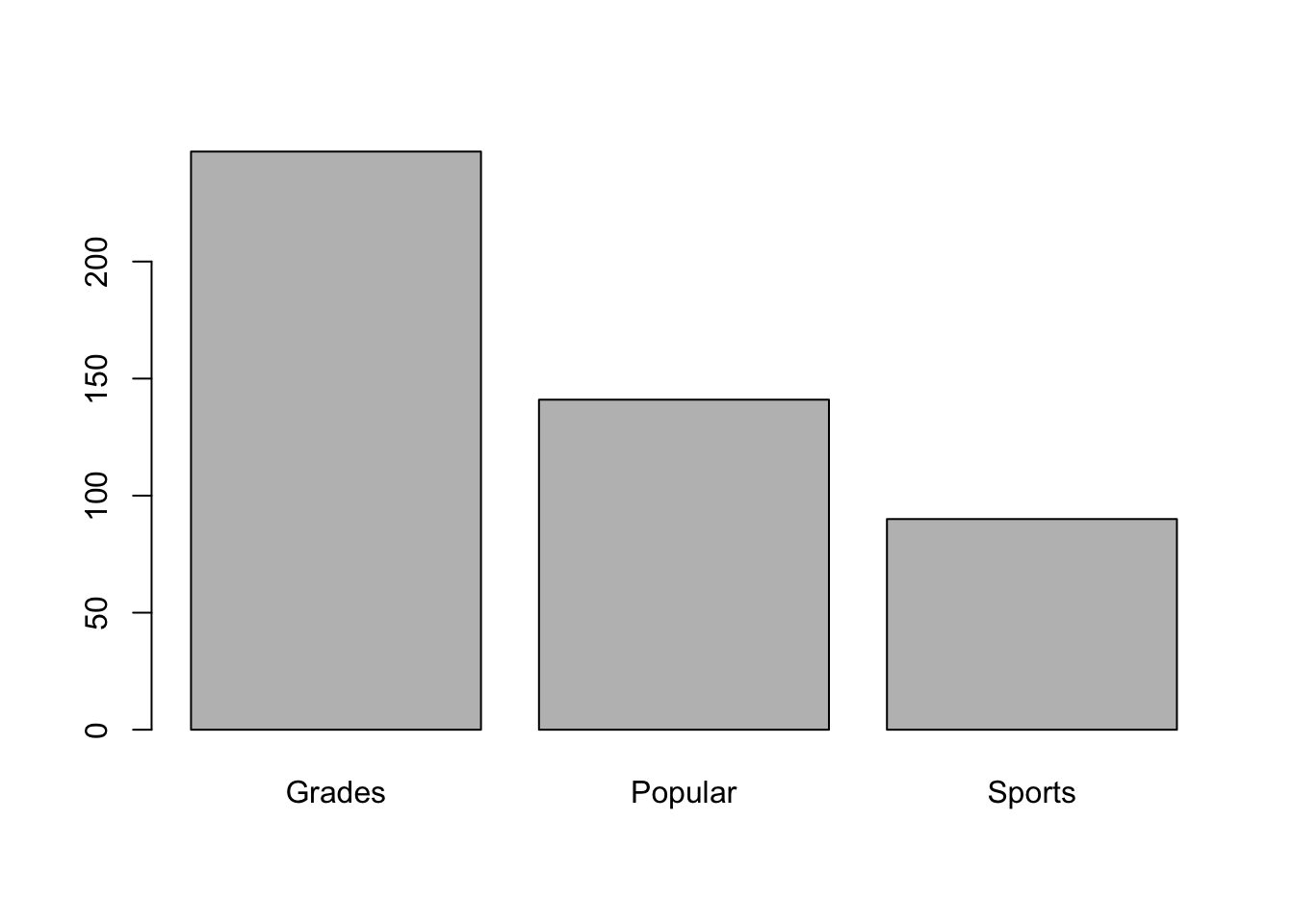

As part of a study, elementary school students were asked which was more important to them: good grades, popularity, or athletic ability. Here is a brief look at the data.

> u.goals <- "https://www.finley-lab.com/files/data/StudentGoals.csv"

> StudentGoals <- read.csv(u.goals, header = TRUE)

> head(StudentGoals) Gender Grade Age Race Type School Goals Grades

1 boy 5 11 White Rural Elm Sports 1

2 boy 5 10 White Rural Elm Popular 2

3 girl 5 11 White Rural Elm Popular 4

4 girl 5 11 White Rural Elm Popular 2

5 girl 5 10 White Rural Elm Popular 4

6 girl 5 11 White Rural Elm Popular 4

Sports Looks Money

1 2 4 3

2 1 4 3

3 3 1 2

4 3 4 1

5 2 1 3

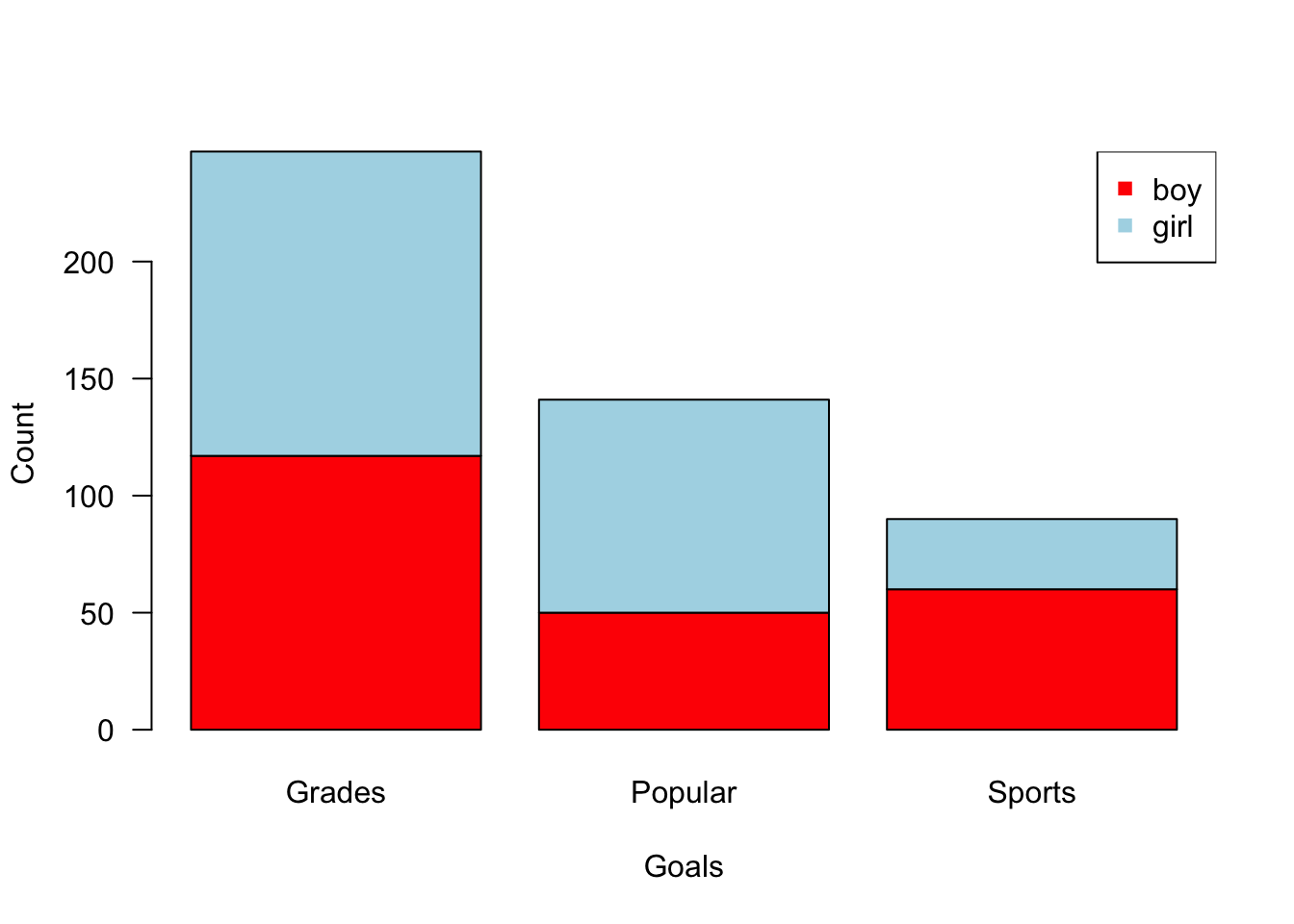

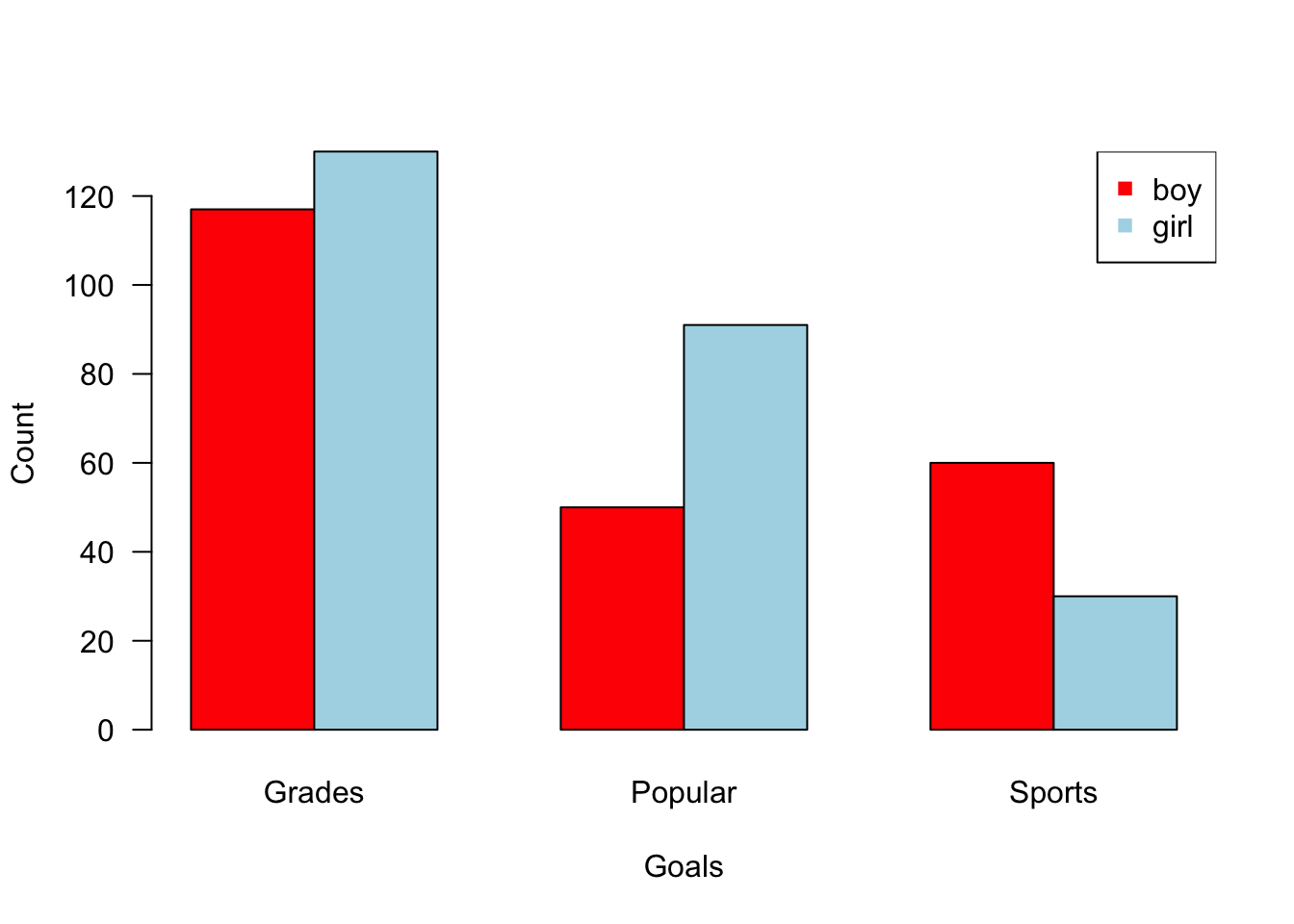

6 2 1 3First, a simple bar graph of the most important goal chosen is drawn, followed by a stacked bar graph which also includes the student’s gender. We then add a side by side bar graph that includes the student’s gender.

Grades Popular Sports

247 141 90

Notice that to create a basic bar graph using the graphics package, we first take our variable of interest StudentGoals$Goals and put it in table format using the table() function. Next we produce a stacked bar graph that also includes the student’s gender. Then we subsequently add a side by side bar graph that includes the student’s gender.

> gender.counts <- table(StudentGoals$Gender, StudentGoals$Goals)

> barplot(gender.counts, col = c("red", "lightblue"), las = 1,

+ ylab = "Count", xlab = "Goals")

> legend(x = "topright", legend = row.names(gender.counts),

+ col = c("red", "lightblue"), pch = 15)

> gender.counts <- table(StudentGoals$Gender, StudentGoals$Goals)

> barplot(gender.counts, col = c("red", "lightblue"), las = 1,

+ ylab = "Count", xlab = "Goals", beside = TRUE)

> legend(x = "topright", legend = row.names(gender.counts),

+ col = c("red", "lightblue"), pch = 15)

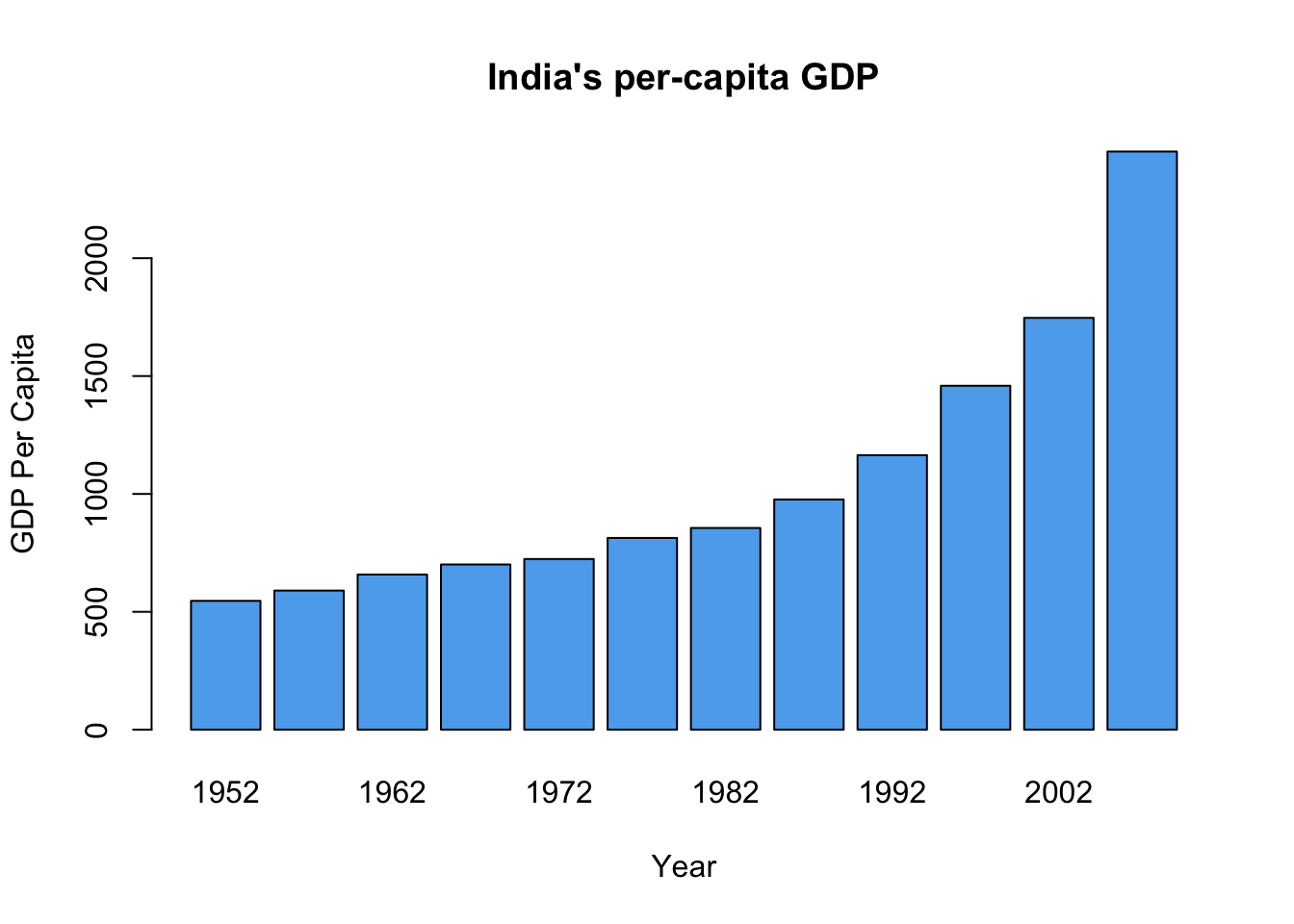

In this example R counted the number of students who had each goal and used these counts as the height of the bars. Sometimes the data contain the bar heights as a variable. For example, we create a bar graph of India’s per capita GDP with separate bars for each year in the data48.

> india <- subset(gapminder, country == "India")

> gdp.india <- india$gdpPercap

> names(gdp.india) <- india$year

> barplot(gdp.india, xlab = "Year", ylab = "GDP Per Capita",

+ main = "India's per-capita GDP", col = "steelblue2")

11.4.4 Graphs of Functions

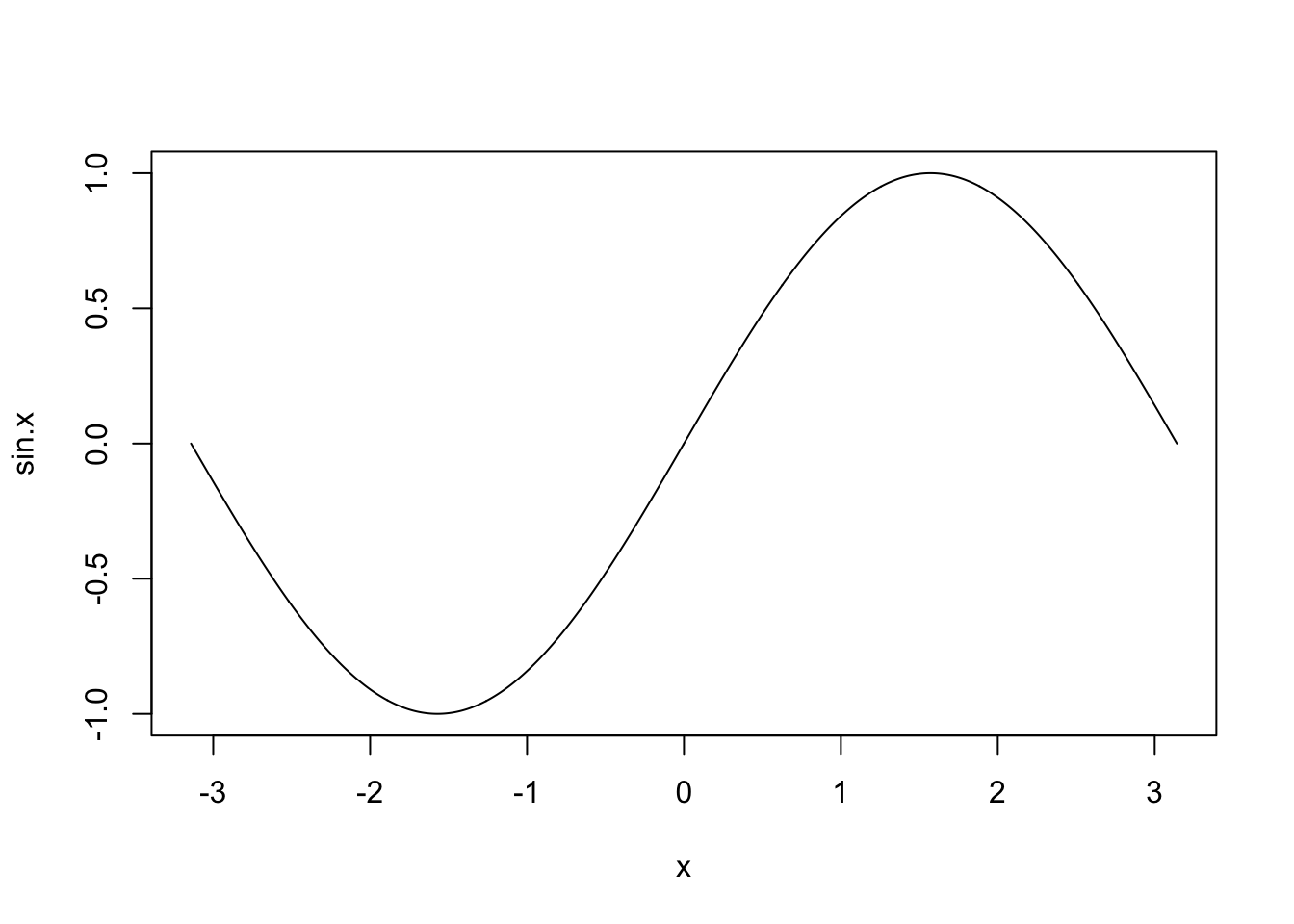

One way to create a plot of a mathematical function \(f\) is to create a data frame with \(x\) values in one column and \(f(x)\) values in another column, and then draw a line plot.

11.5 Saving Graphics

We often want to export our graphics to use in an external document or share with colleagues. There are numerous functions available to export graphic files in different formats. Below we demonstrate the use of the png() function to export the image of the sin curve we created above.

Inside the png() function, we specify the name the image is given when it is saved. There are also arguments to specify the width and height of the saved image. This function opens a png file where the image will be saved. There are analagous functions for other types of files (i.e. pdf(), jpeg()). The second line plot(x, sin.x, type = 'l') simply creates the plot we desire to save. The dev.off() function closes the png file.

11.6 A Summary of Useful graphics Functions and Arguments

Upon initial learning, making plots with the graphics package may seem overwhelming due to the variety of different functions and arguments that control different features of the image that is produced. However, after some practice, you will find that the graphics method of graphing gives you great flexibility in making your images just the way you like them. This flexibility and control is one of the main reasons we produce most of our visualizations using graphics.

Below we provide a summary of the major functions and arguments you may find helpful when working with the graphics package. This is certainly not an exhaustive list, but it does include functions and arguments we often use on a daily basis, so we think you’ll find it useful. One of the nice things about the graphics package is that many of these functions utilize the same arguments.

plot(x, y): the basic plotting function. Many of the graphs you produce will start with theplot()function. Here are some useful arguments (aside from x and y arguments to specify the data):pch: specify the type of point in a scatter plot. We often usepch = 19.xlabandylab: specify the x and y axis labelsxlimandylim: specify the range of the x and y axestype: specify the type of the plot. By default it isp, can create a line plot withtype = 'l'or a scatter plot with lines withtype = 'b'.main: add a title to the plotcex,cex.lab,cex.main: change the sizes of the points, the size of the axis label text, and the size of the title text, respectivelycol: specify the color of the points/linesaxes: ifTRUEaxes will be automatically drawn, ifFALSEno axes will be drawn.

legend(x, y, legend): add a legend to the graph specified by the location(x, y)with the text specified by thelegendargument.points(x, y): add points to an already existing plot. Arguments same as those ofplot().lines(x, y): add lines to an already existing plot. Arguments same as those ofplot().axis(): specify the axestext(x, y): add text to a plot at the location(x, y).par(): function to change a wide variety of graphical parameters for finer control over the plot’s appearance.

The functions listed above certainly do not cover the realm of plots you can produce using the graphics package, but having a good understanding of how to use these functions will give you a firm grip on making publication-quality plots in R.

For additional help, we find that the help pages for most graphics functions are quite helpful. The online documentation for the package available here perhaps provides a more user friendly version of the help pages within R. There are also numerous books and online tutorials available for working with these functions, so a simple google search is often the best way to find additional help :)

11.6.1 Practice Problem

Go to the help page for the par() function (use help(par) or ?par()). Look at the plethora of different arguments that you can use to specialize your plot just the way you like it. List 5 arguments that we didn’t use in this chapter, describe what they do, then use them in a graph using the iris data set (you can use any of the variables in the data set and produce any type of graph you like).

To see the order in which R assigns colors to different values, run the

palette()function↩The “b” stands for “both”. By default, the

typeargument is set to “p” for “points”. You can also specify that you only want lines usingtype = 'l'.↩Note that we could again perhaps simplify this by using a

forloop, but we’ll restrain ourselves until we learn aboutforloops in Chapter 7.↩R offers a large color palette, run

colors()on the console to see a list of color names.↩